Searching for Craig Cignarelli

Searching for Craig Cignarelli

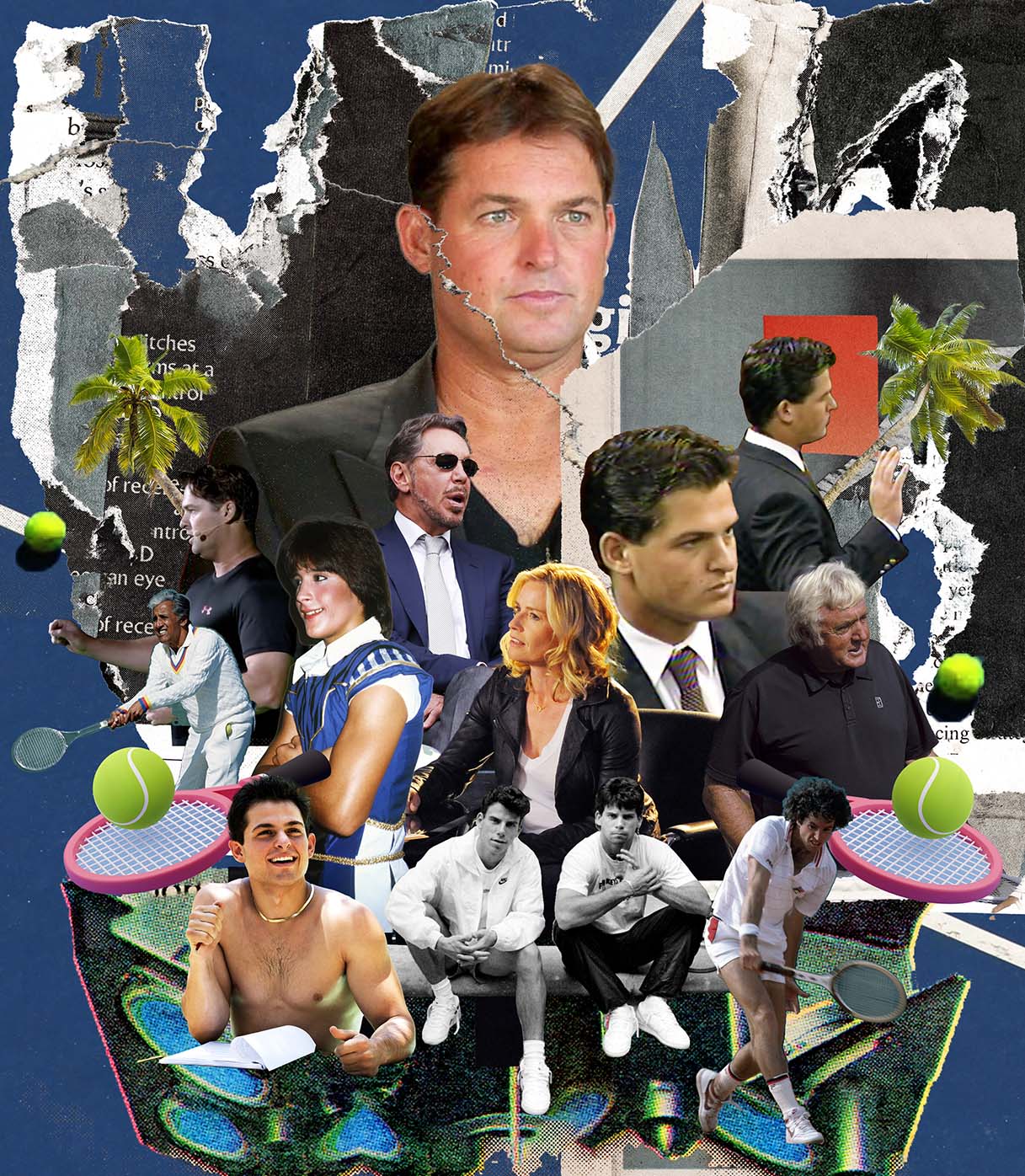

The Menendez trial cast an emotional shadow overa charismatic coach.

The Menendez trial cast an emotional shadow over a charismatic coach.

By Jackson FronsPhoto Illustration by Dakari Akil Featured in Volume 1 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

Searching for Craig Cignarelli

Searching for Craig Cignarelli

The Menendez trial cast an emotional shadow over a charismatic coach.

The Menendez trial cast an emotional shadow over a charismatic coach.

By Jackson FronsPhoto Illustration by Dakari AkilFeatured in Volume 1 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

When I was 19, I beat John McEnroe in a set of doubles. Unsurprisingly, this was the highlight of my first summer home from college. It was 2013, and I spent my mornings driving from Encino to Malibu, first on the 101 to Calabasas, then westward through the canyons toward the California coast. That summer I trained for countless hours on the pristine courts at the Malibu Racquet Club, honing my game under the tutelage of Craig Cignarelli.

Craig was one of a handful of powerhouse coaches on the SoCal tennis scene. The sort of figure with a perpetually full lesson book and an almost cultish following. He was an ample man, California tan, with a round face, bulbous calves, and a stocky upper body. He kept his golden blond hair coiffed in center-parted waves. He’d made his name teaching around the valley in the ’90s, first at the Warner Center then on the courts of Cal State Northridge. After that, he replaced Robert Landsdorp at the Riviera, where he ran the junior program and boasted a list of clients that ranged from touring pros to Elisabeth Shue. One of those pros, Lester Cook, was working with him that summer in Malibu, fresh off a commendable, if not particularly lucrative, career on the Challenger circuit.

Craig and Lester’s Malibu workouts featured a rotating cast of college guys and recent high school grads. People who played for or were soon headed to schools like Pepperdine, Duke, Wake Forest, and UCLA. I didn’t entirely fit in. I was gangly and athletically uninspired. I spent a lot of time staring at my phone. I’d had an up-and-down first season at a small Division III school in rural Vermont and could see the end of my tennis career looming in the not-so-distant future. Off court, I was reading Jesus’ Son and Actual Air, and at night, sore and sunburned, I hung out in the Westwood backyard of my friend’s film-producer father with a cadre of hip liberal arts students who’d long ago given up any involvement with organized sports.

While I’d known many of my training partners in Malibu from our years on the junior circuit, I suddenly felt apart and distant from the tennis world. It was clear that our games (and lives) were trending toward different destinations.

They were long days. We’d hit for hours in the morning. Get Chipotle. Watch Wimbledon on the pro-shop flat-screen. Practice more in the afternoon. Work out in the gym.

It was a common routine with uncommon adornments. Of course there was McEnroe, who waltzed in to get ready for World Team Tennis with some Dunlops and a zip-up hoodie. Another week, Paul Annacone, the ex-coach of Pete Sampras and Roger Federer (and himself an accomplished pro), came as Craig’s guest to bestow his sage wisdom upon us. Annacone eyed me, exhausted, and said, “You really should move your feet more.” Then there was the club itself, a small but elegantly modern facility just off the PCH that no one present would let you forget was owned by Larry Ellison.

I grew up practicing at a much drabber club nominally in Bel-Air, but really on an anonymous stretch of Sepulveda between the Skirball Center and the Getty Center. My coach there, himself a guru with a full lesson book, didn’t possess Cignarelli’s magnetic charisma, cultish following, or glitzy connections. He was gaunt, a bit vulgar, and regularly ducked behind the court to vomit because of an esophageal condition.

Craig was a large part of why I endured the drive, the work, the hours, and the cost (though it was admittedly my parents footing the bill) to practice a sport I increasingly disdained, in a part of town I found annoying.

_________

In Malibu, Craig wore cotton T-shirts and fed balls at an astounding pace with his dilapidated Head Instinct. He possessed a careening and ingratiating mystique and a keen understanding that, in the business of coaching tennis, volume pays the bills. On our breaks, he told stories about Lester battling John Isner and did bits about coaching the kids of celebrities. He was relentlessly smiling, engaged, active, and prepared.

I hadn’t been on court with Craig before that summer in Malibu, but I had known him for years. We met during his tenure at the Riviera when I was in middle school. That was also when I first heard whispers about his place in the violent lore of rich Los Angeles.

That’s to say, while I did improve my game that summer, my interest in the Malibu workouts wasn’t entirely about tennis. I was, consciously or not, beginning the clumsy and careless exhibition undertaken by many privileged and selfish young writers and navigating myself toward experiences that I hoped to one day spin into material.

It’s an impulse Cignarelli might understand. He’s a writer himself. Although his publicly available output consists mostly of articles about tennis, his passions lie in more creative projects. He currently has “four or five different ones in the can,” but he’s yet to pursue publication. He’s “still waiting, we’ll see.”

As a teenager, Cignarelli also wrote a handful of scripts with his friend Erik Menendez. Menendez’s name might be a familiar one to some. He made national headlines for the parental double homicide he committed with his brother Lyle in 1989. Both brothers are currently serving life sentences.

When I Facebook messaged Cignarelli about my intention to write this piece, he asked, before agreeing to an interview, “What type of details would you want? Is it 100% tennis related or are you looking for ancillary topics about your subjects. I am happy to talk tennis all day but personal stuff and extracurriculars don’t interest me.” I told Craig I wanted to learn more about his career in tennis, but also to get a sense of him as a person. I assured him, though, I had no intention of digging into his private life.

On a Zoom call in April, he appeared smiling and in repose on my computer screen, nestled on a sofa in the corner of what looked to be the sunporch of his home outside Charleston, South Carolina. Behind him was a natural sprawl—lush trees and rolling grass. “I’m here with two dogs and a cat,” he told me. His wife and daughter were out of town. It was the first time I’d seen him in more than a decade.

We talked mostly about tennis—his coaching journey, his philosophies, his decision to leave California, and the academy he’s run for the past few years in Mount Pleasant—but we also touched on Craig’s creative and intellectual interests, too. Regardless of the subject, Cignarelli managed the conversation with a writerly control. He eschewed details and dates and, for the most part, steered clear of personal matters.

Craig is a composed and commanding speaker. He’s given quite a few tennis talks over the years, and even done a TEDx presentation. His style is practiced and inflected with bits of mindset jargon—he’s a self-identified “knowledge seeker” who’s given a presentation called “The Long Walk to Excellence” that begins with a glowing reference to manifest destiny. But beneath Craig’s ingratiating charm is an evasive generality. It’s a challenge to pin him down in time or to get the name of a character. He frequently seems to be concealing something, but it’s not clear what or why. When he does tell stories, they reverberate with an allegorical vagueness.

In one, an account of his most memorable coaching experience, a man with terminal lung cancer comes to Craig for a lesson. He used to play as a kid and wanted, at the end of his life, to take up tennis again. “I put him on the baseline,” Craig said. “And he hit the ball about four feet. He just didn’t have any strength…. There was nothing left. He didn’t know how long he had to live. But we worked for a month, almost every day, and after a month he was able to hit the ball over the net and he dropped to his knees and put his arms up in the air and said thank you. About a week later he passed away…. It brings a tear to my eye.”

There are other times, though, when Cignarelli can be far more spontaneous and revealing. During a 2018 Q&A at the USPTA Summer Conference, a member of the audience asked how he got into coaching. Craig smiled and shook his head. “It’s kind of a strange story. When I was 19 years old I was a witness in a really, really famous murder case in California…. My only skill was as a tennis player; to pay that legal bill, I started teaching lessons.”

Coaching tennis isn’t easy work. Although the phrase “tennis coach” might conjure images of doe-eyed morons who lackadaisically feed balls and drone platitudes, in practice the job is often thankless and physically taxing. Coaching elite players is even more daunting. You need to not only be well-versed in the finer (and ever-changing) technical and strategic aspects of the game, but you also have to get those ideas to stick in the skulls of highly competitive, often arrogant, and frequently dim teenagers. That’s before you consider the looming stage parents and the inherently fickle whims of junior tennis players, particularly in a hotbed like Southern California. Hyped coaches and academies come and go like the breeze. Whoever has the new hot thing, the best gaggle of stars, the flashy name, can attract the hoards like moths to a light. Staying near the top of the mountain for more than a generation or two is no easy feat.

_________

Craig Cignarelli is a great tennis coach. That, on its own, is a very impressive accomplishment. It’s also not a position Craig backed into. Unlike many touted junior development wizards, he doesn’t have a name to trade on in the tennis world. He wasn’t a pro. He didn’t make a splash in the juniors. The honor of All-American was never bestowed upon him. He didn’t even play on his college team. The closest thing to a hallmark achievement on Cignarelli’s tennis résumé is a stint as the captain at Calabasas High School.

In his own estimation, Craig was “very average…. I knew nothing…had very little formal training. I had a huge forehand and not much else.”

On our Zoom, Cignarelli confirmed that he started coaching at 19, although he left out the murder-trial part. It was a summer gig at the Warner Center in Woodland Hills, a blustery and dusty tennis complex located on the sixth-story roof of the parking structure of a middling business park. It’s a place I played quite a few tournaments growing up, and I can say firsthand it’s a far cry from the luxe digs of Malibu and the Riviera.

As the story goes (both to me and in the talk for the USPTA), at some point in Craig’s tenure at the Warner Center, he began to work with a girl who showed significant promise. She is never named.

“As she succeeded,” he told me, “I realized I didn’t have the coaching or intellectual tools to stay ahead of her.”

Cignarelli doesn’t enjoy being on his back foot. At a different point in our call, he remarked, “If I don’t know something, I deep-dive into it. I don’t want to be in that position of not knowing…. That manifested in things like going to the French Open a day early to make sure I knew where the practice courts were…where is everything. I didn’t want to feel foolish in front of my player or myself.”

Over the next few years, Craig assembled an impressive “roster of gurus” to learn from. He befriended Eliot Teltscher, he brought his student to Robert Landsdorp for ground strokes and Pete Fischer (pre-arrest for child molestation) for serving lessons.

He sought out guidance from Jose Higueras, Paul Annacone, Pancho Segura, and footwork master Henry Hines.

“I sat there as a sponge…. Number one so I can help her, number two so I can broaden my horizons as a coach.”

The quality of these mentors is as much a testament to Craig’s commitment to the craft as it is to his talent with people. The latter of which is, I think, his greatest gift as a coach.

About his early success, Craig noted, “I had this charisma…. I had a big personality and was loud on the court. A lot of kids gravitated to that kind of program.”

_________

Unlike many charmers, Cignarelli isn’t all bluster. Beneath his warmth, he possesses a calculating and analytical ambition. There’s a duality to Cignarelli I’ve yet to fully reconcile. He’s a boisterous coach who loves to schmooze, but he also goes home and writes, plays chess, and reads Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and David Foster Wallace. He has an astounding attention to detail and an obsession with preparation and routine, yet his recollections of the past are often misty and shrouded in contradictions.

On the tennis court, Cignarelli relies on concrete and definable terms. At the Riviera, he conceived the Grips Program, a concept he pitched and sold nationally. It was basically karate belts but for tennis. The system had players ascend levels by completing a series of output-based skill exams, for example hitting a certain number of forehands out of 10 crosscourt within a certain boundary. These concepts were then deepened and made more challenging by adding stipulations like the ball still needs to be rising as it strikes the back fence. While no junior player ever completed the “black grip” exam to ascend to the program’s highest level, Mats Wilander, on a visit to the club, completed the comprehensive tennis skill assessment with ease. The Grips Program never quite took off.

Craig’s approach, in the early days, was a bit smaller-scale.

“I did my own due diligence,” he said. “I started watching matches and putting dots on a piece of paper where the ball landed. I began to see patterns coming out.”

_________

The timeline during this stage of Craig’s teaching career gets a bit murky. I’m not sure when a lot of this stuff happened, and he isn’t either. I don’t know when the anonymous promising student took her first lesson with him at the Warner Center. I don’t know when he began his quest for tennis knowledge or when he first saw the patterns emerging on the page. I’m also not even sure Craig was 19 when he began coaching. The murder that necessitated the aforementioned trial didn’t even take place until deep into the summer of 1989, meaning Craig either began teaching for reasons entirely unrelated to the trial, or it wasn’t summer, or he wasn’t 19.

None of these details are incredibly important, and I think the fogginess of Craig’s recollection is particularly forgivable because, between August 1989 and March 1996, he had a lot going on.

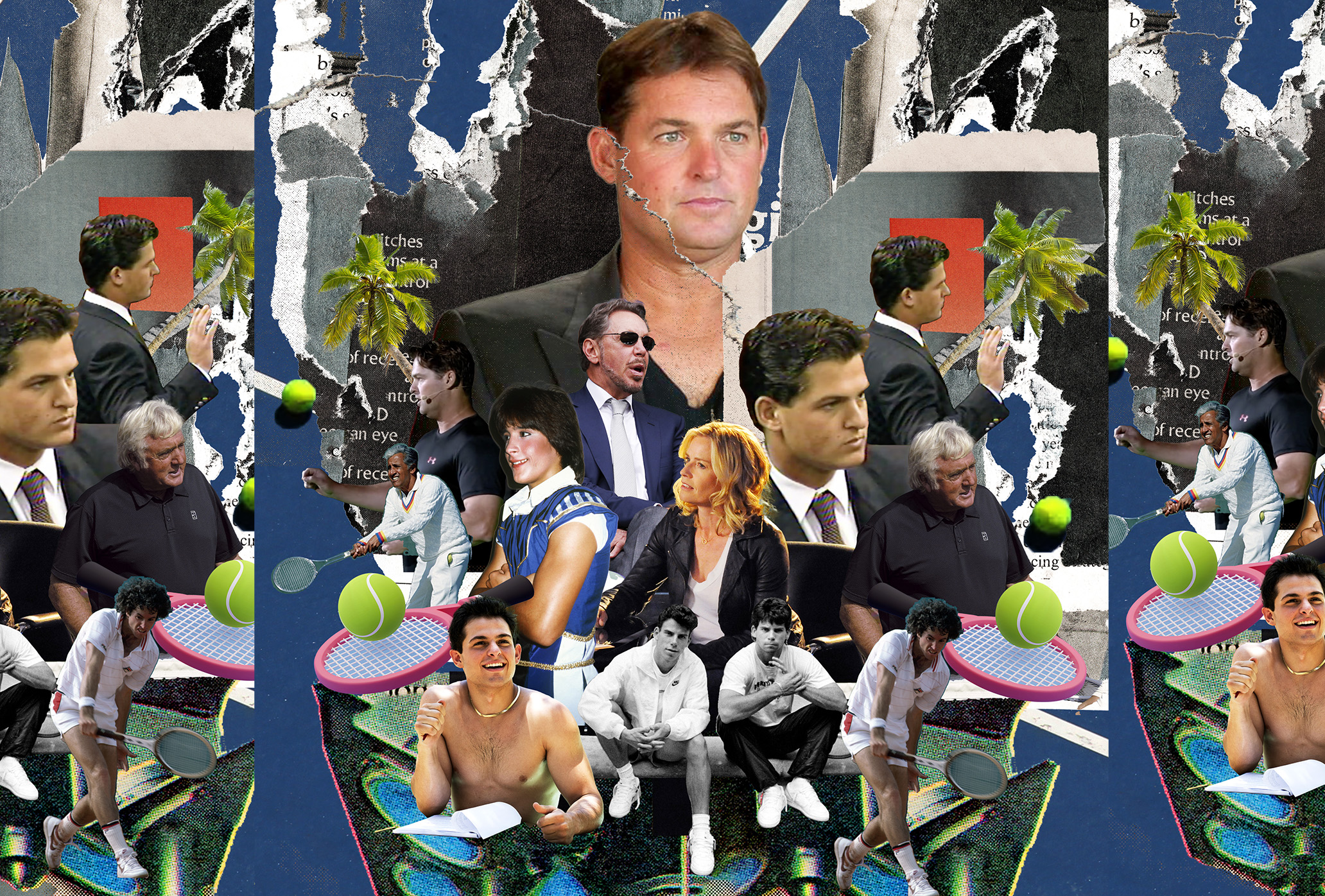

During his tenure as captain of the Calabasas High tennis team, sometime in late 1987 or early 1988, Craig befriended Erik Menendez. They had a lot in common. Menendez had just come west from New Jersey after his father, Jose, took a job at Live Entertainment. Craig made a similar move with his parents as a 10-year-old. They both possessed big personalities, active minds, creative impulses, vast imaginations, and a love of chess. They hit at the tennis club in Calabasas and knew a pro there named Doug Doss. Doss is of no importance to this story other than the fact that, years later, he became the director of tennis at my drab hilltop club with the coach who vomited. Patterns everywhere.

In the same canyons I drove between Calabasas and Malibu, Craig and Erik cruised at night, parking at overlooks off the Mulholland Highway so they could gaze at the ocean and the glittering valley sprawl. They liked to talk about the future. Their aspirations were ambitious if a bit amorphous. Cignarelli said during his testimony that they wanted to “start a company that was multifaceted that dealt in inventions.” He paused. “And screenwriting.” When pressed to clarify further, he added it would be a “corporation.” One that dealt in “stocks, inventions, corporate takeovers. Anything we could do to develop our status in society.” Cignarelli also contemplated a political career, along with “having a side hobby writing law screenplays and definitely going to law school.” He ultimately wished to be a senator.

These dreams were both erased and memorialized in court depositions after Erik Menendez and his older brother Lyle murdered their parents, Jose and Kitty, on Aug. 20, 1989, not long after Erik returned from playing the Boys’ 18 and Under National Championships in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Some weeks later, standing in the foyer of the family’s Beverly Hills home, the same home where the killings occurred, Erik confessed to Craig.

_________

I don’t intend to do any criminal sleuthing. It was a famous case at the time and one that’s been narrativized and re-documented ad nauseam. I’m far from a court reporter, and I’m not a fan of the lurid voyeurism of true crime. However, the case has reentered the public consciousness of late.

Last year, the brothers filed for a retrial, claiming the murders occurred in self-defense, the result of a lifetime of verbal, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse at the hands of their father. While Jose’s sexual abuse of Erik was a key piece of the defense team’s case at the trial, the murders have, more often than not, been framed as an act of greed perpetrated by two spoiled and out-of-control young adults after a fat inheritance. New evidence has further corroborated the brothers’ claims and reframed the story.

Roy Rosselló, a former member of the boy band Menudo, with whom Jose Menendez worked during his time at RCA Records, revealed that when he was 14, the elder Menendez drugged and raped him. These revelations were the focus of a three-part Peacock docuseries, Menendez + Menudo: Boys Betrayed. This year, the case was the subject of an episode of48 Hours titled “The Menendez Brothers’ Fight for Freedom” that first aired on March 3. Finally, the forthcoming second season of Netflix’s Monsters will narrativize the murders, with Javier Bardem and Chloë Sevigny cast as Jose and Kitty Menendez. Charlie Hall, the son of Julia Louis-Dreyfus, will take up the role of Cignarelli.

I would guess these are the extracurriculars Craig didn’t want taking over the narrative of this piece. I can understand why. I’m sure the murders and the trial cast an emotional shadow over large portions of his life, and they continue to cast a very literal shadow over his Google search results. However, as a journalist (and a hound for material), I would be remiss not to mention them. While Craig is often reduced to a footnote in the Menendez saga or recognized for his coaching prowess, these two parts of his character are rarely, if ever, reconciled. I would also add I haven’t gone digging into Cignarelli’s private life; all of this is alarmingly public.

Online, it’s not hard to find a ravenous and active community of Menendez enthusiasts still picking apart the trial and the murders. Cignarelli is a regular topic of conversation. To many of these weirdos, Craig is a villain who “betrayed Erik.” These people seem to mostly be para-social freaks who’ve over-empathized with two guys who killed their parents. Certainly, Jose Menendez was a monster, but that also isn’t Craig’s fault.

It is also true that there’s a natural human impulse to speculate on this kind of thing—to find the patterns—particularly because the case contains so many alluring and absurd details. For example, Craig and Erik coauthored a script that opens with a son killing his parents to inherit an insurance payout.

It’s a matter Craig described like this to ABC News in 2017: “I remember talking about the opening scene…. ‘We need to establish a crime. We need to have the protagonist gain an inheritance so he can actually fulfill his dream of creating this hunting ground for humans.’”

At the trial, Craig made a striking impression. He was young and handsome then. Thinner than he is now and outfitted in a suit jacket with gold buttons. Multifaceted conglomerates and political aspirations aside, he had an arrogant streak, a defiant smirk, and more than a few glib answers. During the cross-examination, he also bungled some dates, and his memory frequently got foggy. He also conducted himself memorably off the stand. Writing in the October 1993 edition of Vanity Fair, Dominick Dunne remarked, “On the two days Craig Cignarelli testified in court, he showed up with two young, pretty girls in miniskirts, who giggled a lot.”

Being a pompous dumbass at 19, however, is far from a crime. If it were, I’d be guilty too. His fate in all this is a small tragedy in a much bigger tragedy.

_________

The six-year trial material disrupted a formative time in Craig’s life. It paused his education and thrust him into the public eye. There’s also the emotional mess of your best friend committing a wildly violent double homicide, abuse or not. His course was redirected by the actions of another person he had no control over.

In his 2017 interview with ABC, Craig spoke openly and candidly about the strange catharsis of the trial ending: “Honestly, when the second jury came back with a guilty verdict, there was a part of me which just said, ‘I’m done. It’s finally over.’ And it felt like there was this sense of relief, followed by this really strange feeling of sadness. Like, wow, it’s finally closed, and I actually have just lost my best friend for life. He’s going to be sitting in a jail cell for the next 50 years.”

Whatever you think of him, there’s nothing fair about that. I wonder what Craig’s life might look like if the murders never took place. While I’m not sure he’d be running a multinational inventions and screenwriting firm while also serving in the Senate, it’s the necessity of asking the question that casts a glum cloud over what he has accomplished.

I’ve coached tennis before and, like writing, it is a consumptive task. Standing in the sun while yelling isn’t a bad way to escape yourself. At his peak, Craig taught 12- and 13-hour days.

Coaching tennis is a human endeavor, too. As Craig puts it, “an act of service.” You meet people where they are, attuning the lesson to their physical, mental, and emotional states. But it is also a defined and bounded relationship. There are confines to the court, the lesson begins and ends, and there are the walls between the teacher and the students, too. “My role is to stay positive, to teach, to mentor…. Then there’s that line. Because you don’t want to play the role of a parent, but you want to play the role of someone the kids can trust.” In the same way these professional relationships are delineated, Craig imposes a similar separation upon himself.

“When the door closes on the gate to the facility and I get back into my own personal mode, which is a little more introverted…I want to read books…play chess. The things that I enjoy are a little more intellectually challenging. And I try to find those intellectual challenges on the court. But I think for me it’s a quieter life at home, and the person that comes out on the court is because I had to create this character…this figure…who’s someone who’s going to be charismatic and pulling you forward. I think as a person I get my charge from that and my rest time at home.”

While I do understand the sentiment here—we are all, in our various ways, performing ourselves in the world—these boundaries between the personal and the professional can’t be so easily delineated. A lawyer doesn’t transmute into a different person when she arrives at the courtroom. A tennis coach’s soul doesn’t alter when he latches the gate and rolls his basket to the service line. I don’t stop being me when I sit down to write. It’s all personal and it all isn’t. It’s all the character and it’s all you.

On the page, the writer is the one in control. It’s a fixed space. One with limits. It’s a place to figure things out. While Craig never brought up Erik Menendez to me, he did bring up one of his past writing projects that caused me, immediately, to think of his former friend. Cignarelli described it as, “Young Dexter goes to Hogwarts. A school for serial killers who train to kill serial killers.”

Adolescent monsters killing older, bigger monsters.

_________

Craig left California around 2015, making a stop in Atlanta before settling in South Carolina. He told me the taxes got too high. The traffic was getting worse. He saw “decay happening,” but I wonder if a fresh start in the South appealed for other reasons, too. Memories can ghost a landscape. He seems to like his new life more.

“The tennis in California is very much like the culture of the city. It’s first strike, what can I get from you, how big is your wallet, what do you drive, what can I take from you? Are you a producer? Can I do a film?… I’d had enough celebrity, Lamborghinis, and Ferraris.”

It’s different where he is now, and he’s different too.

“Out here you feel like someone wants to give you a hug and invite you into the house. I feel like I had to take some of my guard down to settle in out here. I can finally breathe a little.”

The move has also changed his approach both as a coach and as a writer.

“I think the biggest growth for me has been understanding how much it really is the impact you have on the human being, as opposed to their successes on the court…. For me the thing that changed the most was that at first I was thinking, ‘How good can I make players?’ It was very ego-driven. Now it’s about, does this kid have life skills?… Did we give them solutions so they can face any problem that comes up?”

On the page, the pulp and violence have been replaced with far more heartwarming material. One of his more recent projects is a series of “about 150 chronicles” that he wrote for his daughter as she was growing up. “Three to four paragraphs a day… I compared her first steps to Neil Armstrong walking on the moon.”

Although Cignarelli seems at peace with his family and his pets, he still withholds, intentionally or not. Some of the guard is still up, but maybe that’s just because I was there on the other screen looking for a quote, some shape, a detail that might unlock him and give his life a deeper meaning.

There was one moment, near the end of our call, when that happened.

“I’ll give you a quick one story,” Cignarelli said. It was a final strange allegory. This one had nothing to do with tennis, although I wonder who the nameless guy was.

It goes like this:

“I flew back on a flight from Sacramento one time, and I was with a guy and he invited me to breakfast a couple days later. And we went up to a tower where the mayor was having breakfast and a bunch of other people were sitting in there. I was 18 years old. I’d come there in a suit for one of the first times in my life. And we all sit down and have breakfast and I pull out cash to pay for the check, and the guy just kind of taps my head and said, ‘We don’t do cash here.’ And I felt so naive. It was such a brutal feeling to not know how to function in these surroundings, and I think that inspired me to make sure that I’m always aware of how things work. Because I don’t ever want that feeling again.”

TENNIS. ART. CULTURE. FASHION. TRAVEL. IDEAS. — SIGN UP

RECOMMENDED

Postcard from Adelaide ’26

ADELAIDE

Taylor Fritz Sees the Game Differently

UNITED CUP

The Price is Tight

AUSTRALIAN OPEN