A Dangerous Mind

A Dangerous Mind

A review of Searching for Novak by Mark Hodgkinson.

A review of Searching for Novak by Mark Hodgkinson.

By Patrick J. SauerAugust 28, 2024

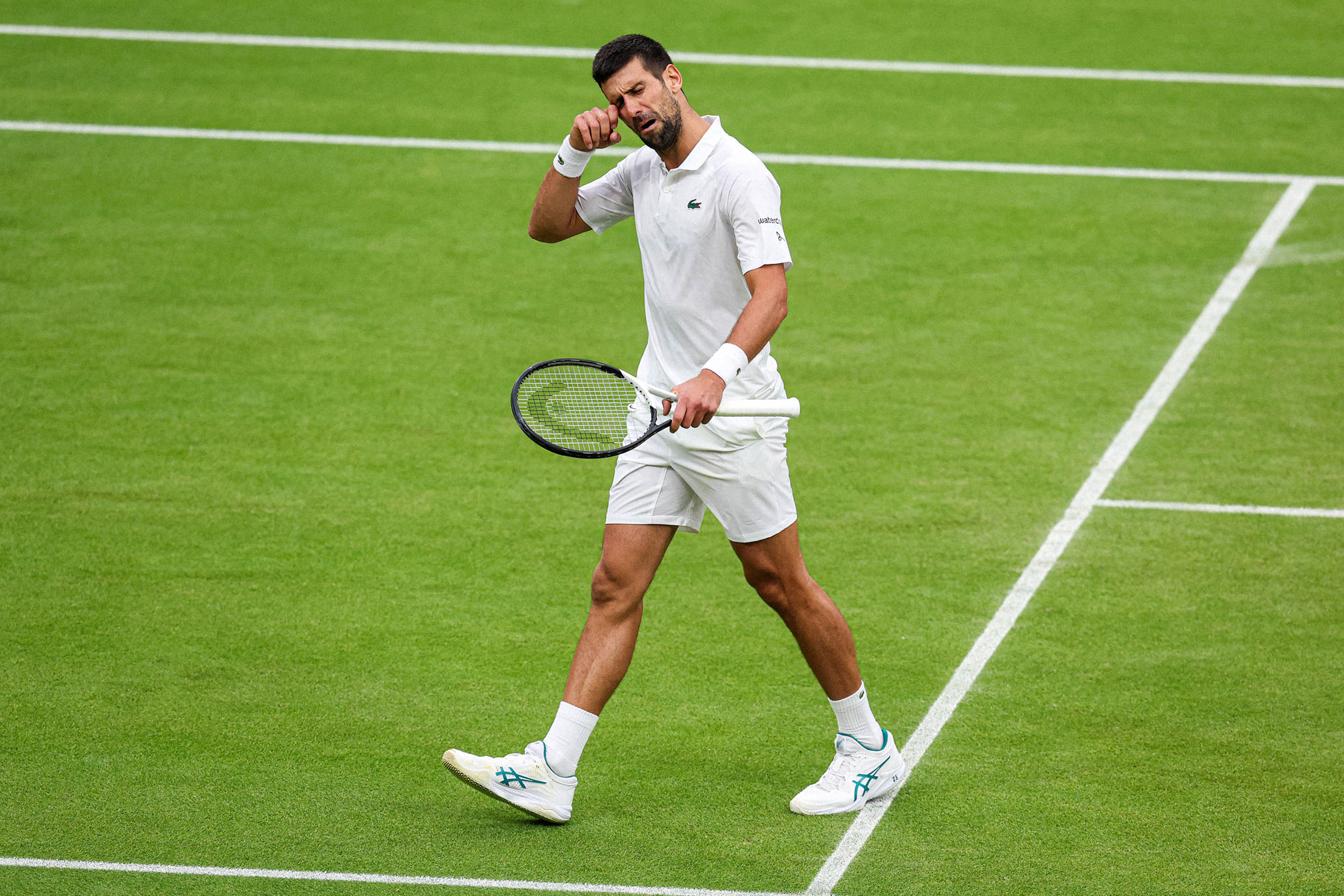

Novak Djokovic pulls a crying face to the crowd after he is booed during the Wimbledon semis in 2023. “When the crowd’s down on Djokovic, his blood is up, and he has the special Serbian type of dark energy,” writes Hodgkinson // Getty

Novak Djokovic pulls a crying face to the crowd after he is booed during the Wimbledon semis in 2023. “When the crowd’s down on Djokovic, his blood is up, and he has the special Serbian type of dark energy,” writes Hodgkinson // Getty

A funny thing happened to me on the way to Novak Djokovic’s Olympic gold. For the first time, I found myself cheering for him. Not in a fist-pumping “Lettttttt’ssss goooooooo!!!!” kind of way; more in cap-tipping, “Goddamn, you’ve done it all. There are no tennis mountains left to scale” astonishment. I’ve never been on the extreme end of the anti-Novakkers, the Fedal stans who never got over the Serbian skunk at their lawn garden party, but I’ve actively rooted against his tying and breaking Serena’s Slam mark. So much for that.

What is it about Novak Djokovic that makes him, in my anecdotal estimation, the least loved all-time world-class athlete of my 50-odd years on earth, the Belgrade diaspora notwithstanding? If styles make the fights, he’s the best counterpuncher the sport has seen, with agility that feels like he was bitten by a radioactive spider. And yet I’m hoping Carlos Alcaraz goes on a five-year Grand Slam tear. So color me intrigued by Searching for Novak: The Man Behind the Enigma from British tennis writer Mark Hodgkinson, which purports to be the “first serious analysis” of Djokovic. What I found is a book mystifying and infuriating in equal measure, but one that certainly had me seeing the man in a new refracted light. He really puts the thwack in thwackadoodle.

The book opens strong, as the author takes readers inside the cold, cramped concrete shelter where, in 1999, an 11-year-old Novak and his family bugged out for 78 consecutive nights of NATO bombings. In a harrowing scene, Hodgkinson writes that after a few minutes he craved air and natural light, but even more astounding was that war-torn Serbia didn’t slow down young Novak one bit. Every day, he would figure out what parks weren’t covered in rubble and, since school was shuttered, play tennis until the sun set, and so did he, down in the bunker. The horrors of war sparked a competitive fire in him, a thirst for revenge he took to the courts.

It fueled him early on, and Searching for Novak is at its best as he rises through the ranks up through 2010, covering the highly entertaining Djoker impersonations, anxiety management through incessant ball-bouncing, and how there were once grumblings he faked injuries and ailments to drop out of losing matches. That ended when he stopped eating gluten. There’s a whole chapter about it. Hodgkinson divides Novak’s career into the before/after wheat protein binary, which is fitting, because in the second half of the book, I became allergic to bullshit.

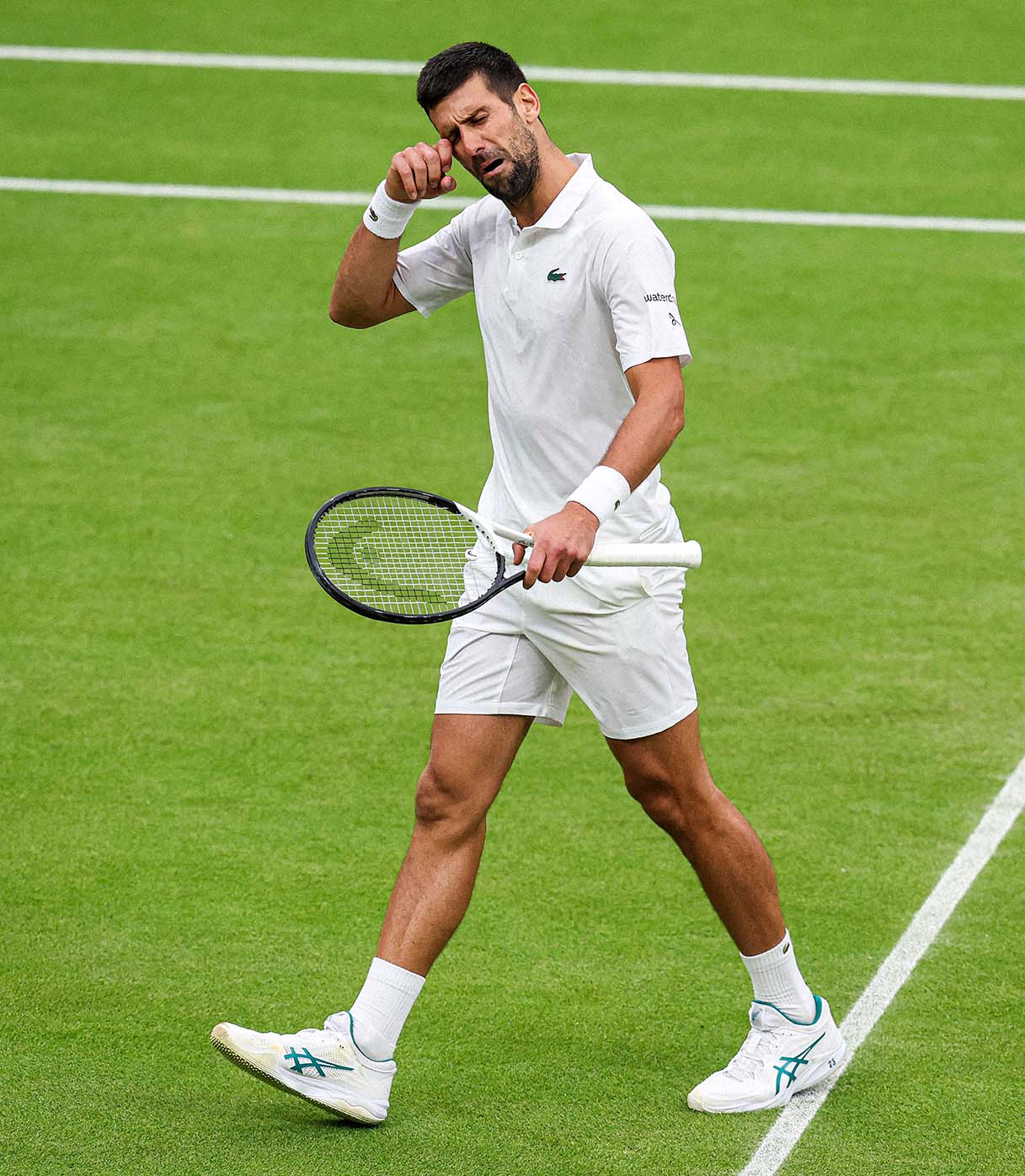

Some of Novak’s bonkers beliefs—or at least ones proffered by people who have his ear—make for a good time. My favorite comes from Semir Osmanagic, a fedora-wearing Bosnian archaeologist who in 2005 said he discovered “the Pyramids of the Sun, the Moon, the Dragon and Love,” and suggested water found beneath it “enhances Djokovic intellectually and emotionally.” Novak thought it a good idea to join Osmanagic—a man “a group of Bosnian academics have appealed to their government to stop, saying he is embarrassing to the country”—down 82 feet into tunnels with 52-degree chest-high water “without any safety rails or support,” just some protective waterproof gear. Magic Pyramid Water, definitely worth risking a Wimbledon grass snack for.

Novak with archaeologist Semir Osmanagic at the “Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun" in Visoko, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2020. // Alamy

Novak with archaeologist Semir Osmanagic at the “Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun" in Visoko, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2020. // Alamy

There are so many amusing nutty details in Searching for Novak, like the time he set an alarm to remind himself it had been a year since he had eaten a small piece of dark chocolate, but the book is also awash in credulity. Hodgkinson says point blank in the intro that Djokovic “has the most original mind in tennis, perhaps across all sports,” and then notes multiple times that he doesn’t read newspapers or watch television news. If you know nothing, then you know everything. See, an enigma.

Other primo nuggets include: “When the crowd’s down on Djokovic, his blood is up, and he has the special Serbian type of dark energy” (not a thing); “He’s not an entitled tennis diva. He’s not being difficult and demanding for the sake of it” (give or take a US Open line judge); and “He’s the future billionaire who hardly cares for money” (I’ll see your balderdash and raise you mansions on multiple continents).

Too often, Searching for Novak has the feel of one of those ghostwritten business or tech books where a mediocre white man has final say on his genius on the page. Obviously, Novak isn’t one of those guys, he’s on a GOAT short list—although Hodgkinson stating he absolutely is because “you have to go with the hard data on who has won the most majors” isn’t exactly “smart analysis”—but the constant fluffing from every talking head, including luminaries like Chris Evert, makes Novak less sympathetic and way more insufferable.

A case for tennis immortality can be made, but the man doesn’t walk on water. Oh, but wait, a boyhood coach says Novak has a mental energy that “goes somewhere over the line which belongs to God, to the creator.” And a “former advisor on nutrition and life” says of his homie, “Maybe it’s not the best comparison but look at Jesus. He was also exposed and punished by officials at the time.”

Of course the latter comment was in regards to Novak not getting the Covid jab, a section of the book in which the fun, weird Novak-galaxy brain took a dark personal turn and brought back my peak pandemic rage all over again. In the chapter “Prison Life,” Hodgkinson makes Novak’s time being detained in a crappy motel out to be a Melbourne version of Midnight Express. I’m sure it was a grungy hell for the “unlawful non-citizens” (aka refugees and asylum seekers) stuck in tiny rooms and eating industrial cafeteria food for years. Novak was there for five days with a laptop, exercise equipment, and gluten-free grub. Not a diva.

The chapter that follows, “The Villain of the World,” is an entire section of quackery from every corner of Novak’s coterie, including himself. Hodgkinson writes that Novak didn’t regret “being unvaccinated and everything that came with it.” Cool. You know what came with it for me? Putting on a hazmat suit and holding my mother’s hand in a New Jersey hospital room as she died while we were literally watching Joe Biden’s national pre-inauguration Covid mourning ceremony. But hey, Hodgkinson intimates that it’s understandable a man who treats his body like a temple wouldn’t take the shot, and besides, Novak’s old pal Idiotana Jones had thoughts about how “high levels of negative ions in the tunnels beneath the Bosnian pyramids would have boosted his immunity against Covid,” and that “we don’t know the content of the experimental genetical pharmaceutical product, but I do know the content of what’s happening in the tunnels.”

You know what? I think I’m done searching for Novak. An enigma? Maybe. A jackass? Definitely. Let’s go, Carlitos.