All That Love

All That Love

Jamaican tennis pioneer Richard Russellalways did things big.

Jamaican tennis pioneer Richard Russell always did things big.

By Ben RothenbergFebruary 27, 2025

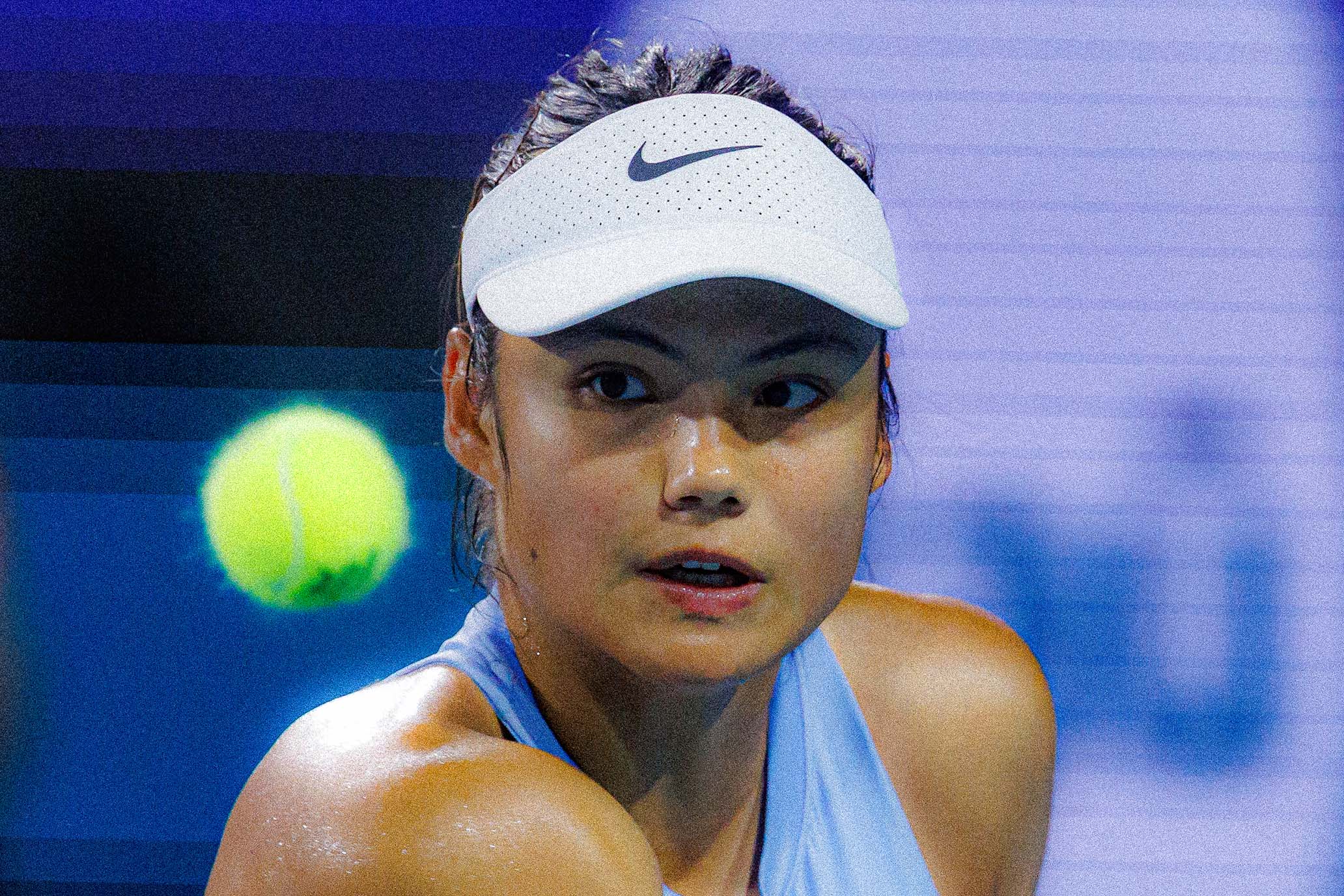

Peak Richard Russell in Jamaica (bottom right with doubles partner Lance Lumsden). //Courtesy of Compton Russell

Peak Richard Russell in Jamaica (bottom right with doubles partner Lance Lumsden). //Courtesy of Compton Russell

Richard Russell, an athletic Jamaican teenager, was on track to become a cricket star of the 1960s for the West Indies—or so he thought, until one day he was plucked off the cricket field at his high school, Kingston College, by a teacher who needed players for the school’s undermanned tennis team.

Once he showed potential on court, the tennis coach entered him in the Jamaican National Tennis Championships; he reached the final.

From there, Russell—and his family—rebuilt their lives around tennis. His father, Irving, scuttled long-held plans to build a swimming pool at the family home in Kingston, installing a tennis court instead. His mother, with some annoyance, had to replant her imported roses on another side of the house to make room.

“At 21 Wellington Drive, Kingston, Jamaica, that became the Russell House of Tennis,” Compton Russell, a nephew of Richard’s, told me. The home court was convenient but compact; its perimeter was well below regulation size. “Bro, the runback was about five feet short on each side,” Compton said, laughing.

But the small concrete rectangle was big enough to become a launching pad: Richard developed into Jamaica’s national champion and the best player in the Caribbean. The question, though, was where to go into orbit. Peter Scholl, a German coach who was a protégé of Gottfried von Cramm’s, had been in Jamaica for a spell, but Russell would need to leave the island to find his potential. The rampant segregation still present in the nearby United States made an American path a less viable option.

Seeing how the best players in the world were Australian, Irving Russell cold-called—after being patched through several operators across the world—legendary Australian coach Harry Hopman, telling him he was the father of the Jamaican national champion who had nowhere to train. Hopman said to send Richard over to Australia, and so Richard went.

“He goes to Australia, and Harry Hopman falls in love with him,” Compton Russell recalled.

Richard Russell lived in Hopman’s Melbourne home for a year. His letters back home—which took weeks to arrive—recounted training sessions with Laver, Emerson, Newcombe, Sedgman, and more. So sublime was Russell’s technique on his Eastern-grip forehand and one-handed backhand, Hopman even wound up using Russell as a model in some of his instructional videos. After Australia, the entire world of tennis was open to Russell, and he charted his course.

“His legacy to me is the fact that he really had the courage to go out there and play in the early days when there was no guarantee that anybody could make a living out of playing tennis,” David Tate, a Jamaican who was an early tour companion of Russell’s, told me. “He was a pioneer.”

Making a lucrative living playing tennis was expressly forbidden in those days, in fact, as the most prestigious tournaments remained closed to professionals. So to keep the tennis dream going, the Russell family back in Jamaica hosted barbecue fundraisers on the family tennis court. There was even a sort of proto-crowdfunding: an ad placed in a Kingston newspaper saying that Russell was accepting donations.

“I remember his dad talking about second mortgages,” Compton Russell told me. “Just to get some money, a loan, for air tickets and hotels.”

The Russell hustle back home was propelling a player who, despite modest results, was becoming one of the most beloved players on the traveling tennis tour. To have some fun and make some extra cash on the road, Russell agreed to join his compatriot Lance Lumsden in a musical duo that performed at various stops along the tour, with a signature song called the “Tennis Twin Medley.”

In those years predating the ATP rankings, tournament invitations often largely focused on national and regional champions; Russell, as the best of the Caribbean, got invited to the biggest tournaments. He won a decent share of his matches, too, including a main-draw match at each of the four majors.

“He beat some really well-recognized players,” Compton Russell told me, suggesting an analogue: “In today’s game, Richard would have had a win over somebody like a Tsitsipas.”

The flashiest win on Russell’s résumé came in doubles: In 1966, Russell and Lance Lumsden pulled off a considerable upset in a live Davis Cup doubles rubber in a zonal match in Kingston against the Americans, beating Arthur Ashe and Charlie Pasarell 6–4, 7–9, 14–12, 4–6, 6–4.

Ashe and Russell were easily lumped together as the two top Black players on the circuit; one article in The Louisiana Weekly introduced Russell as “the world’s second ranked black tennis player,” behind Ashe. (“The handsome champion of the West Indies is a speed demon on the court with his ‘Go for broke’ style,” it added.)

Russell was often mistaken for Ashe by autograph seekers at tournaments and learned it was easier if he just signed “Arthur Ashe” without making a fuss. But Russell and Ashe also formed a genuine friendship; Ashe visited Russell in Jamaica multiple times.

Some of Russell’s visits to America, though, proved more challenging in the mid-1960s. One tournament in Pensacola, Fla., held an emergency board meeting to decide whether or not to let this Black Jamaican man play at their all-white club.

“They decided that I’m not an American, I’m Jamaican, and those are the grounds on which they allowed me to play,” Russell told BlackTennisPros.com decades later, upon the occasion of his induction into the Black Tennis Hall of Fame.

Compton Russell recalled Richard sharing a more menacing memory. At a tournament in the Carolinas, Richard was sitting in the back seat of a car, being driven home by the white daughter and son of his host family at that week’s tournament.

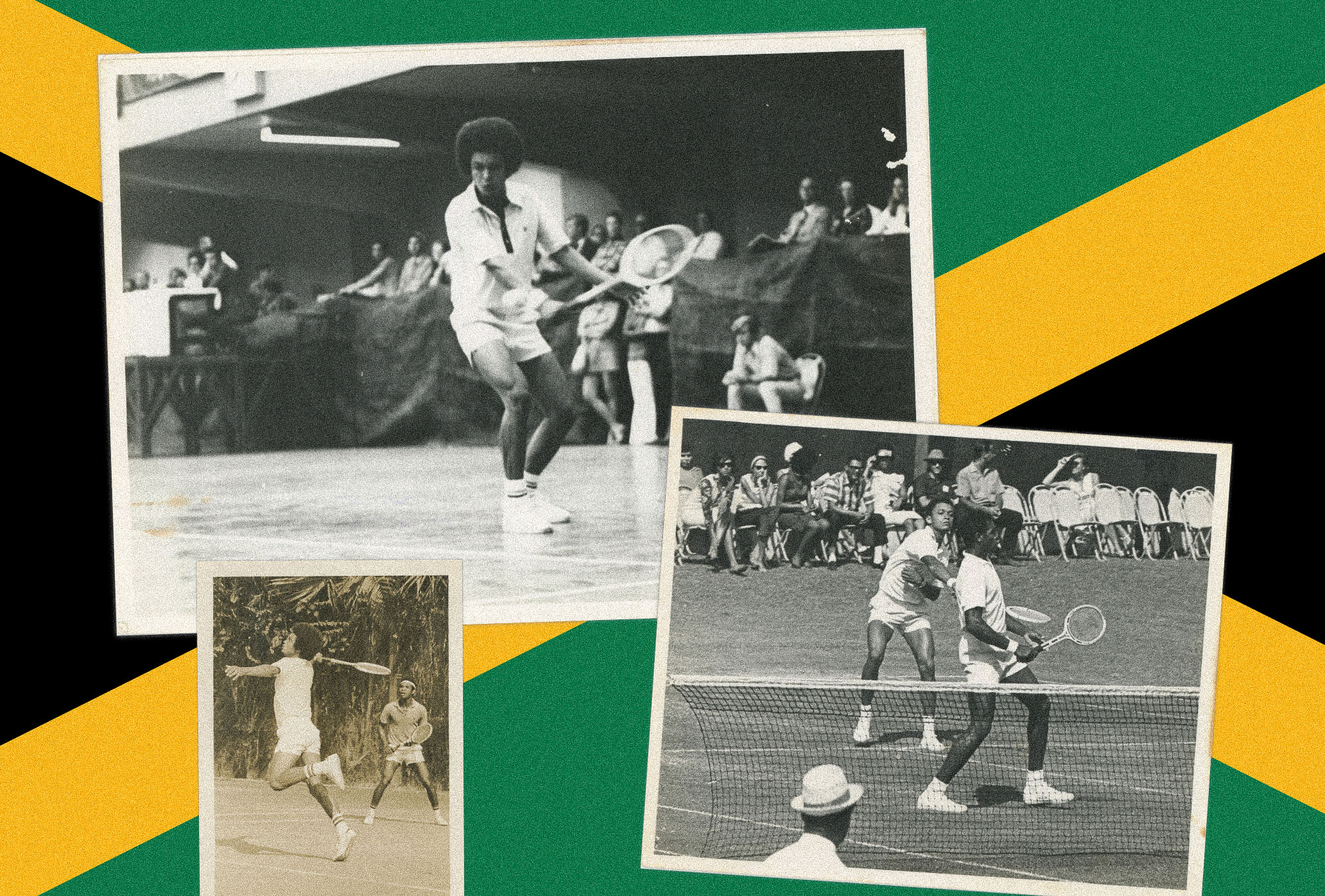

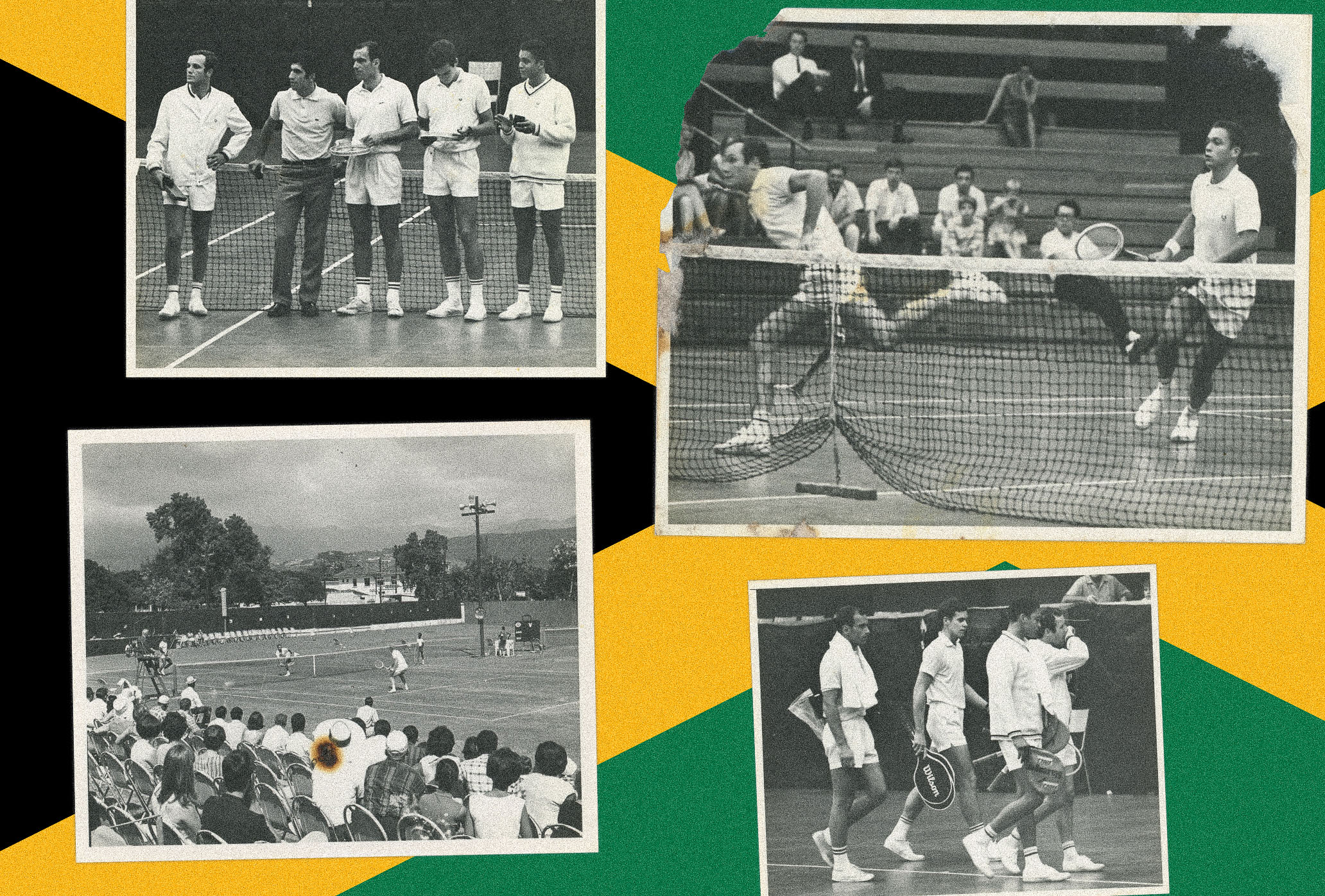

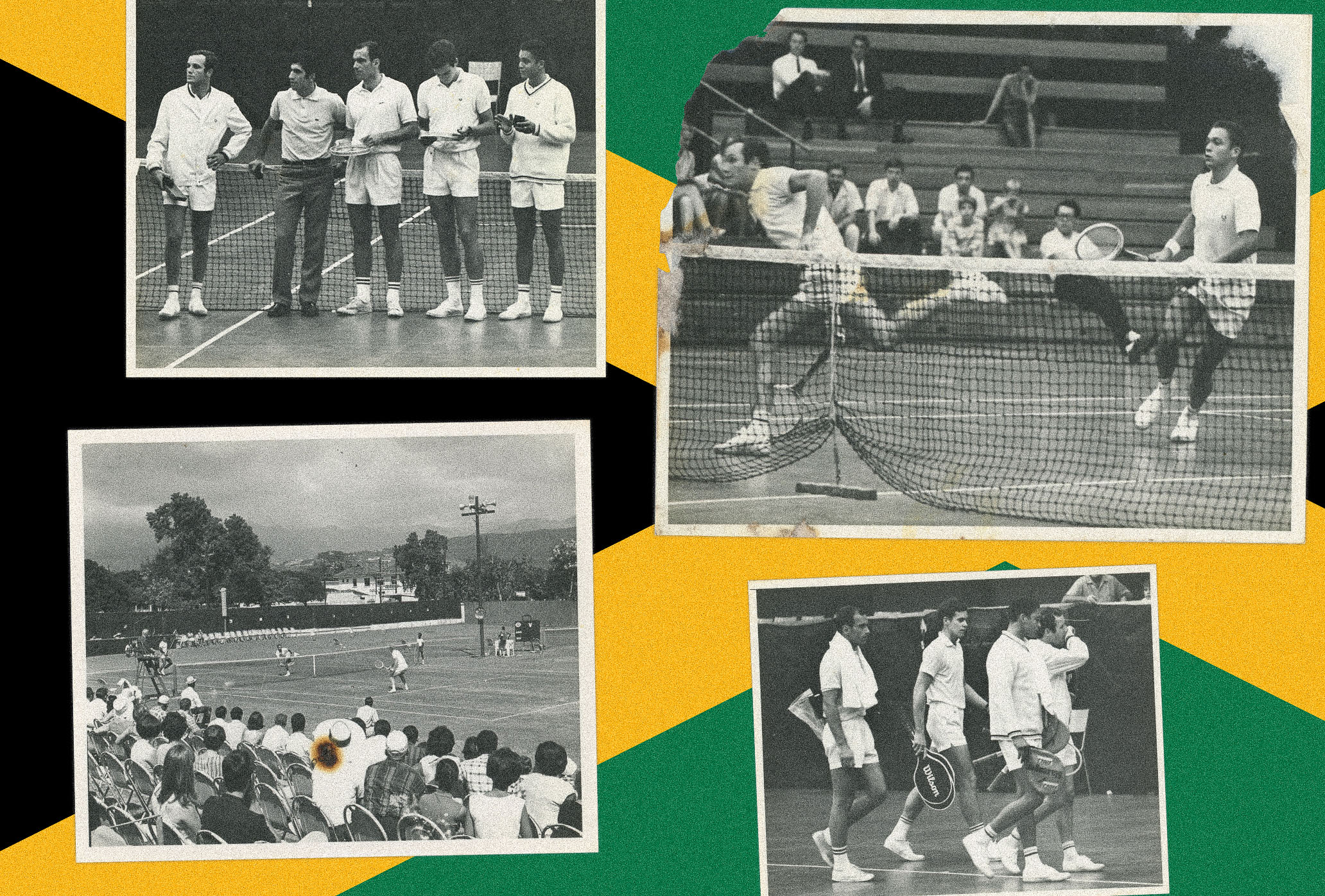

Richard Russell (far right) at the pro tournament he helped organize at the National Arena in Kingston in the early 70s. Top right: with doubles partner Tom Okker. Bottom left: tennis on the old grass courts at the St. Andrew Club in Kingston. // Compton Russell

Richard Russell (far right) at the pro tournament he helped organize at the National Arena in Kingston in the early 70s. Top right: with doubles partner Tom Okker. Bottom left: tennis on the old grass courts at the St. Andrew Club in Kingston. // Compton Russell

“They stopped at a red light, and a car pulled up beside him,” Compton told me. “The other car was packed with guys, and they rolled the window down and started yelling. The girl was driving the car. She took off, and the car started following them. They raced around for two or three miles, pulled in the driveway of the house. And as they pulled into the driveway of the house, the brother and sister jumped out of the car. The other guys pulled right on the roadside beside them.”

The sister and brother, Compton recounted, told Richard to stay in the car as they jumped out to talk down the threatening group: “They explained: ‘He’s not an American; we’re hosting him for a week, and it’s okay. You’d be very wrong to attack him or persecute him. He’s protected. He’s an international athlete. And if anything happens, it’s going to be a big problem.’ And they drove away.

“He only told me a few stories like that,” Compton added. “He never really focused on it in a sense. He was tennis, tennis, tennis, tennis, tennis, tennis, you know?”

Because within the world of tennis, life was pretty good for Richard Russell. Compton, eight years younger, joined Richard on the tour in the early ’70s and got to see his magic up close.

“That’s when I see the aura,” Compton said. “I’m tagging along, and I’m in awe. The tournament directors, the players, the tournament referees, the linesmen, the hosts, the families: ‘Richard, you’re back! So nice to see you, Richard! Oh man, what are you doing later? You’ve got to come to dinner. We’ve got to have lunch.’ All that love—he was larger than life. A bright light.”

Richard’s status as a role model spread beyond his family, beyond Jamaica, and to the rest of the Caribbean commonwealth islands, who used to compete together as one Davis Cup team at that time.

“It meant everything because it showed that one of us could do it,” Mike Nanton of St. Vincent told me. “He gave us a goal to move towards, knowing that we could get there too.”

John Maginley, an Antiguan, said that Russell was “everything I wanted to be.”

“Just his presence, the way he carried himself on the court, off the court,” Maginley said. “He was always immaculately dressed. Spoke very well. Carried himself very well. You never heard of Richard Russell being in anything crazy, in any trouble.”

Maginley and others described Russell as their “icon,” but one who was always approachable and engaged with their own fledgling careers.

“Very simply put, he wasn’t a snob,” John Antonas of the Bahamas said of Richard. “He shared everything. In tennis, when Richard was good, things weren’t quite as they are today; everybody there, they shared everything. We were a family.”

Russell was on the ground floor when men’s professional tennis was being built into a towering business: He became a founding member of the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) when it was created in 1972, a calling card that remains a point of pride for Jamaican tennis.

But the shift toward commercialism wasn’t always what he wanted. With his more laid-back approach, Russell grew weary as the Open Era and rankings arrived and the tour became more professionalized, competitive, and demanding. He decamped home for a lucrative coaching gig in Half Moon Bay in Montego Bay; his $100-an-hour lessons were described by one as “like celebrity hour.” He once ushered the professional tour to his own island home, hosting a 1978 WCT Tournament in Montego Bay that featured top stars like John McEnroe and Ilie Nastase.

But while he was giving lessons to vacationing millionaires like the Bronfman family, who founded Seagram’s, Russell also found ways to foster local talent. He initiated a program where kids could make $1 an hour being ball boys and ball girls during the lessons; when the courts weren’t in use by resort guests, the kids were free to play on their own.

“That’s how a lot of us got good,” Maureen Rankine told me. Rankine said her family, “from our neighborhood, didn’t belong in tennis.” But with Russell’s support, she and four of her siblings from the “wrong side of the tracks” went to colleges in the U.S. on full tennis scholarships.

Richard Russell soon had his own sons, Ryan and Rayne, whose tennis-playing careers he wanted to develop. In order to help his sons thrive, Richard organized a bevy of small professional tournaments in Jamaica, as many as 22 in 2002, striking deals with various hotels around the island. The biggest beneficiary, as it happened, was from outside his own family.

“Everything was made available by Mr. Russell for the sons,” Dustin Brown told me. “And yeah, I was fortunate enough to be around, to also be under the wing, almost, just gliding and trying to take all this stuff that could help my career.”

Brown, who switched to representing Germany and later switched back to representing Jamaica at the end of his career, would go on to be the region’s best player of this century, highlighted by a thrilling win over Rafael Nadal in the second round of Wimbledon in 2015.

“Who knows what would have happened if those Futures wouldn’t have been in Jamaica?” Brown told me. “Maybe it would have been no Dustin Brown—you never know.”

Brown said that he hadn’t known of Richard Russell’s own playing career until it started being mentioned in articles to contextualize his own milestone wins at majors. “He was very chill, friendly, and calm,” Brown recalled. “But you knew that he had a lot of pull in Jamaica.”

Another future star had a start in Russell’s Jamaica too. In 2011, just before her 14th birthday, Naomi Osaka traveled from her home in Florida to make her debut at a $10k tournament Russell had organized in Montego Bay. I spoke to Richard in 2022 as I researched a biography of Osaka. He apologetically said he didn’t remember Osaka’s appearance well—not surprising since she lost in the first round of qualifying—but said he took pride in what she’d become from her own Jamaican launching pad.

“We were very pleased and pleasantly surprised and very, very happy that a player like her came to Jamaica early and then became a world-class player,” he said.

In our conversation, Russell told me that girls were going to be a focus of his going forward. “I got a call last year from a tennis coach at a college in Louisville, Kentucky, asking me if I have any female Usain Bolts playing tennis,” Russell said, laughing. “And that was very funny. We recognize now we want to focus first on very athletic female youngsters and introduce them to tennis. I think that’s where we’re heading, as a small country.”

Russell was recovering from two cancers when we spoke, he told me, but he remained driven and full of plans for future ventures. Maureen Rankine, who described herself as Russell’s “His Girl Friday,” said that up until his death, Russell had “plans to continue doing things big.”

Richard Russell died from pneumonia on Jan. 15, 2025, in Montego Bay at the age of 79. His funeral, with an all-white dress code in a nod to Wimbledon, will be held on March 1.

His passing has rekindled email chains and memories among the men whom Russell played alongside across the Caribbean, many of whom have now dispersed to other parts of North America.

“Whatever you write about Richard, put in there that the guy was loved by his fellow guys,” John Maginley told me. “I think that’s the most important message, that we’re in awe of all that he did.”

The Hopper

—CLAY Tennis on Beatriz Haddad Maia’s US Open run.

—Giri on Iga Swiatek’s loss to Jess Pegula.

—Jon Wertheim’s mailbag is full this week.

—Sara Errani and Andrea Vavasori have won the US Open mixed doubles.

—Tim Newcomb on Taylor Fritz and Asics.