Back from the Grind

Back from the Grind

Book Review: The Racket, by Conor Niland

Book Review: The Racket, by Conor Niland

By Patrick J. SauerJanuary 22, 2025

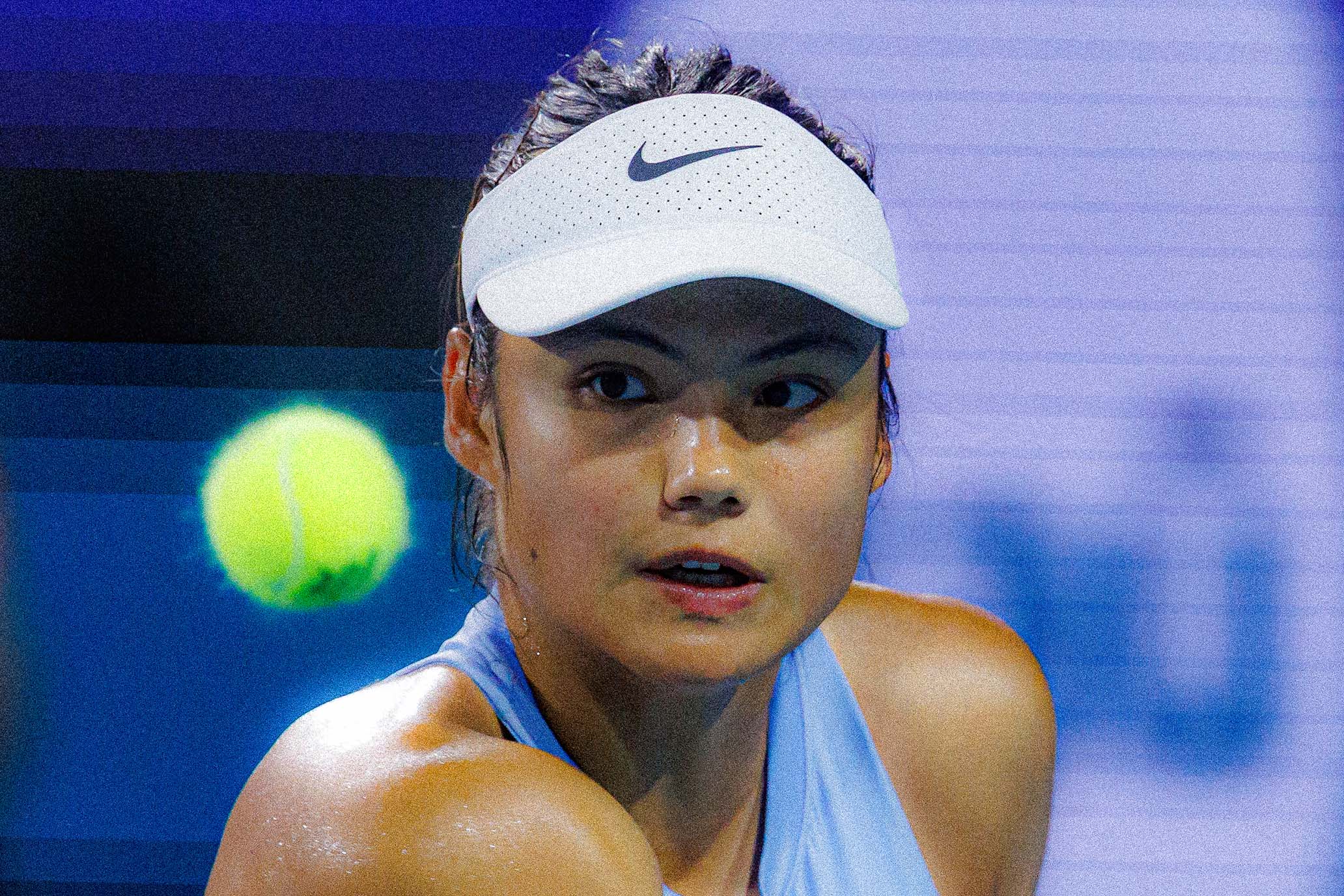

Ireland Davis Cup captain and author Conor Niland // Getty

Ireland Davis Cup captain and author Conor Niland // Getty

Before we collectively embark on our 2025 tennis safari, there’s something we all need to do. Close our eyes, take a deep breath, and contemplate for a moment what it truly means to be the 129th-ranked player on the ATP Tour.

Let’s start by pointing out the obvious. Reaching #129 is an incredible achievement in and of itself, putting the owner of that ranking—held at the start of the Australian Open by 21-year-old Jaime Faria of Portugal—in rarefied air. It’s a ranking well within the somewhat arbitrary, but nonetheless long-standing, Top 150 upper echelon. And yet, #129 is a far cry from the more tennisly salient Top 100, which places the practitioner squarely on the ATP Tour with a now-guaranteed $300,000 basic income. A #129 ranking means trodding the lesser tours, a singular track in which dwelling amongst the 99th percentile—being better at this impossible game than nearly everyone on the planet—requires beating the bushes in front of few fans for little to no money, all in the hopes of climbing the points ladder. Where maybe, just maybe, you claw your way to playing an early-exit center-court millionaire-superstar-warm-up match at a major.

It’s a life Conor Niland, the greatest male tennis player Ireland has ever produced, knew all too well. In 2010, he topped out at #129 but managed to battle his way to an Arthur Ashe showdown against Novak Djokovic in the opening round of the 2011 U.S. Open. Unfortunately, with less than zero margin of error, Niland lost the physical battle with a night-before-the-match meal described as a “pork salad” and had to retire in the second set down 6–0, 5–1. Niland may have thrown up his chance at tennis immortality, but he can take pride in stealing a game off Novak, who went on to win his first of four U.S. Open chips. (Quick refresher on how insane Djoker’s career has been, he beat debutant Faria in the second round of the Aussie last week.)

Niland lays out his seven-year professional odyssey in The Racket: On Tour With Tennis’s Golden Generation—and the Other 99%, the deserving winner of the 2024 William Hill Sports Book of the Year. Niland’s blisters-and-all memoir is an ace, the liveliest craic about the struggles of life on the tennis margins I’ve come across. The Racket serves up a killer mesh of gallows humor and glorious heartbreak, a clear-eyed portrait of the liminal no-man’s-land where Niland was light-years from onetime peer Roger Federer (head-to-head teenage record; Niland 1, Fed 0), and also theoretically within a handful of lucky break points, of crossing the magical Top 100 threshold. Alas, as Niland says, he and every other tennis player have “a deep and lasting relationship with their highest ranking.” Niland’s numbers don’t lie, but it turns out, when told by a first-rate prosesmith, the journey to the middle—from #1,325 at 19 to calling it a #1,041 day at 31—is as fascinating and mystifying as one to the top of the tennis universe.

Along the way, Niland reached the stars, getting a mutual-respect social media boost from fellow non-Brit Andy Murray, helping get Niland a Wimbledon wild card, and hitting with 16-year-old #25-ranked Serena Williams at the Bollettieri Academy. In both cases, Niland quickly crashed back to Earth. In 2011, as the first Irishman to play at Wimbledon in 30 years, he choked away a 4–1 final-set lead to France’s Adrian Mannarino—a contest that warrants its own excruciating chapter, “The Longest Day”—dooming his dream Federer rematch on Centre’s holy grass. Still, Niland fulfilled his personal prophecy, which morphed from a childhood fantasy of winning Wimbledon to the more prosaic professional goal of simply playing there.

Oh, and over two hours of ground strokes, Serena never asked Niland what his name was. Win some, lose a whole lot more.

Fitting his Celtic roots, the no-tennis-ball-can-to-piss-in blarney is as thick and creamy as a pint of stout. (No joke, Niland describes the constant battle to find quality practice balls at sub-tier events as “reliably painful.”) The Irish is strong in The Racket. It feels like a story best unspooled over many nights in front of the fireplace at the pub, beginning with the fact Niland rose up from the streets of Limerick in the first place. Given the sport’s Victorian English origins, the Emerald Isle apparently has as much love and respect for tennis as the Queen Mum’s remains—there were no clay courts in Ireland in Niland’s era—and the country offered small potatoes support-wise. A lack of funds and an institutional buttress runs throughout The Racket, as Niland matter-of-factly details how after finishing up a flush college run at Cal-Berkeley, he was on his own.

Fellow countryman George Bernard Shaw once wrote, “My way of joking is to tell the truth. It’s the funniest joke in the world.” Niland takes that dictum straight to The Racket’s pages, laying out step-by-step how a Challengers existence puts future prestige to rest and becomes solely about making ends meet. Niland avoiding extraneous expenses by washing his kit in the bathtub, surviving on the free protein bars, and calculating whether it’s worth tanking a match to avoid flight-change penalties became the norm. But so did living up to the tennis wannabe’s mantra, “Keep working hard, it will happen,” which means travel, travel, and more travel. That ain’t cheap. At one point, Niland jets from Dublin to Doha hoping to secure an open slot, only to end up trying to convince himself a few Qatari practice rounds and a bit of ruddy face time with whatever governing organizer types were around was worth it. (Spoiler: It wasn’t.)

Niland’s intense low-level schedule shouldn’t be called a grind because that word has inexplicably gained positive pro-worker mindset connotations in certain circles. So we’ll go with “slog.” At his peak, the slog led to playing in 68 tourneys over 85 weeks, in places only the most dedicated cartophiles would recognize, like La Palma, Bucaramanga, Prostejov, Braunschweig, and Houston. Niland endured a bone-chilling –37 temp to play indoors in literal Siberia and battled debilitating 95-degree outdoor heat in Greece. The wildest chase of a precious ATP ranking point involved a seven-hour taxi ride across Uzbekistan with the luggage in his lap and a driver who took an extended lunch break. All for the glory of a Facebook post to a handful of followers back home, one declaring a Niland Bosnian flameout with the brilliant back-page tabloid headline “Conor is…Banjaxed in Banja Luka.”

Beyond the money, the starker reality of The Racket is there was none of the expected camaraderie to make the slog even a wee bit less lonely. Nope. Guys drank by themselves, because God forbid a player get a leg up knowing an opponent is slightly hungover instead of enjoying an entertaining night with the lads. After seven years on tour, Niland retains zero friendships despite crossing paths with countless dudes around his age surviving that brutal tennis life. As he describes it, making a name for oneself on the ITF World Tennis Tour or Challengers circuit isn’t about tennis abilities, “it’s about being able to cope with the strange bedfellows of regular boredom and constant uncertainty. Not many succeed.” And even fewer get the unrequited thrill of almost smashing a Zendaya threesome.

Niland would get his brief celebrity shine after the Novak crap-out, even appearing on an RTE talk show featuring Cuba Gooding Jr., Sinéad O’Connor, and McLovin, but it’s not like he was Stephen Cluxton or Noel Skehan or some kind of big shot. Niland claims contentment just by having gotten out of tennis without a “reflex resentment” of the game, impressive given his pretax earnings over those seven years amounted to $247,686. Do the math. Or don’t. It’s depressing. Therein, though, lies the brilliance of The Racket, and it can be calculated.

Even as a literary sports character, Niland isn’t an archetype. He’s not Rocky Balboa, a down-and-out ham-and-egger who gets his one do-or-die championship shot and seizes it. Nor is he Roy “Tin Cup” McAvoy, a supremely talented Icarus who can’t get out of his own way and flies too close to the 18th green. Neither underdog nor overdog, Conor Niland was a tennis stalwart who simply fell a cut below the top dogs and lived to tell the tale. The current captain of Ireland’s Davis Cup team made his peace—and a hell of a memoir—with all #129 of it:

I don’t believe it’s a contradiction to say that I didn’t fulfill my potential while also saying I couldn’t have tried any harder.

Fair to say, he’s already fulfilled his potential as a writer. Certainly, the irony of a tennis nobody possibly earning recognition and acclaim for being one such fella won’t be lost on his Gaelic wit. Good on ’ya, lad. Reflecting upon the book, what shines through in The Racket didn’t leave me shaking my head and pining for what Conor Niland’s career might have been. It left me nodding in respect for what it was.