Leave Blood on the Court

Leave Blood on the Court

It is always possible to find an Australian-related tennis anniversary.

It is always possible to find an Australian-related tennis anniversary.

Joel Drucker

July 10, 2024

Leave Blood on the Court

Leave Blood

on the Court

It is always possible to find an Australian-related tennis anniversary.

It is always possible to find an Australian-related tennis anniversary.

Joel Drucker

July 10, 2024

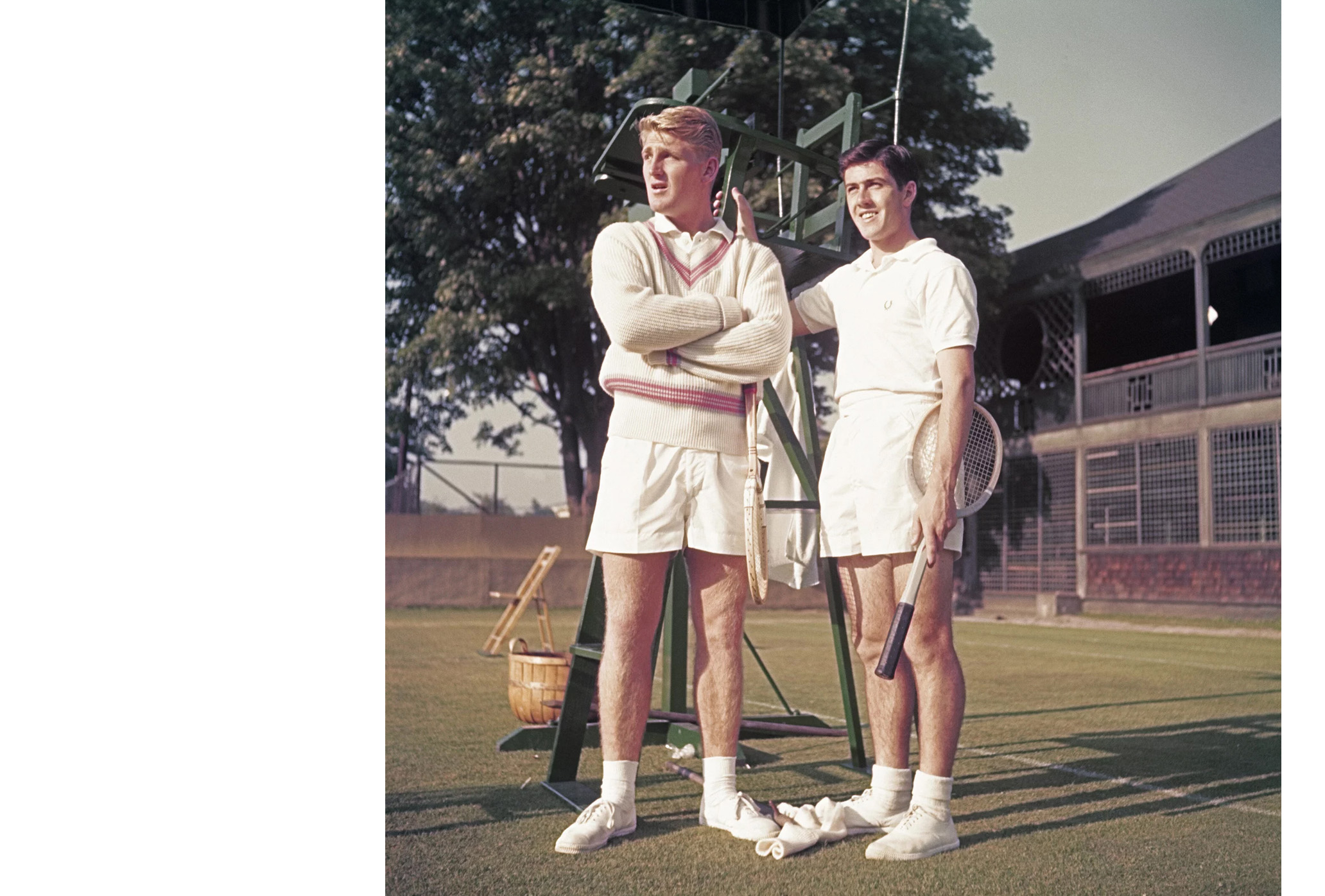

Lew Hoad and Ken Rosewall photographed by Slim Aarons // Getty

Lew Hoad and Ken Rosewall photographed by Slim Aarons // Getty

On a rainy Friday night in SW19, a five-minute walk from the All England Club, approximately 250 Australians gathered for a mid-tournament party conducted by Tennis Australia to celebrate a number of Wimbledon anniversaries. Festivities and history: a perfect Aussie tennis combo.

It’s been 20 years since Rennae Stubbs won her second women’s doubles title; 30 years since the Woodies earned their second of six at the All England Club; 40 years since Wendy Turnbull took the mixed; 50 years since Ken Rosewall reached his fourth Wimbledon singles final, the John Newcombe–Tony Roche duo won the Wimbledon men’s doubles title for the fifth time, and Evonne Goolagong took the women’s doubles; 60 years since Roy Emerson’s first of two singles victories, Fred Stolle captured the men’s doubles, and Margaret Smith Court and Lesley Turner Bowrey earned the women’s doubles. Turner Bowrey and Stolle in ’64 also won the mixed.

Those accomplishments were the party’s theoretical news hook. Of course, it’s always possible to find an Australian-related tennis anniversary. Many subcultures have their certain exemplars. In winemaking, there’s France. In painting, Italy. In tennis, no nation more than Australia personifies tennis’ supreme values. Emerson, winner of a men’s record 28 Grand Slam titles, articulates those principles as well as anyone: “Leave blood on the court or don’t bother playing,” goes one signature recommendation from the man lovingly nicknamed “Emmo.” Another addresses sportsmanship: “If you’re injured, don’t play. But if you’re not injured, there are no excuses.” And one particularly cutting comment from this friendliest of nations: “I have never played him when he was well.” But in the bigger picture, in the world of Australian tennis, words always take a back seat to action.

Less than 12 hours after attending Friday night’s party, I engaged in one of my favorite Wimbledon rituals. Many a Wimbledon morning, I’ll arrive on the grounds of the All England Club sometime between 8 and 10, take a seat on the vacated Centre Court, put on my headphones, listen to some personally meaningful music, and ponder the heart and soul of tennis. As Newcombe likes to say, “Centre Court is where you’ll be asked all of life’s questions.”

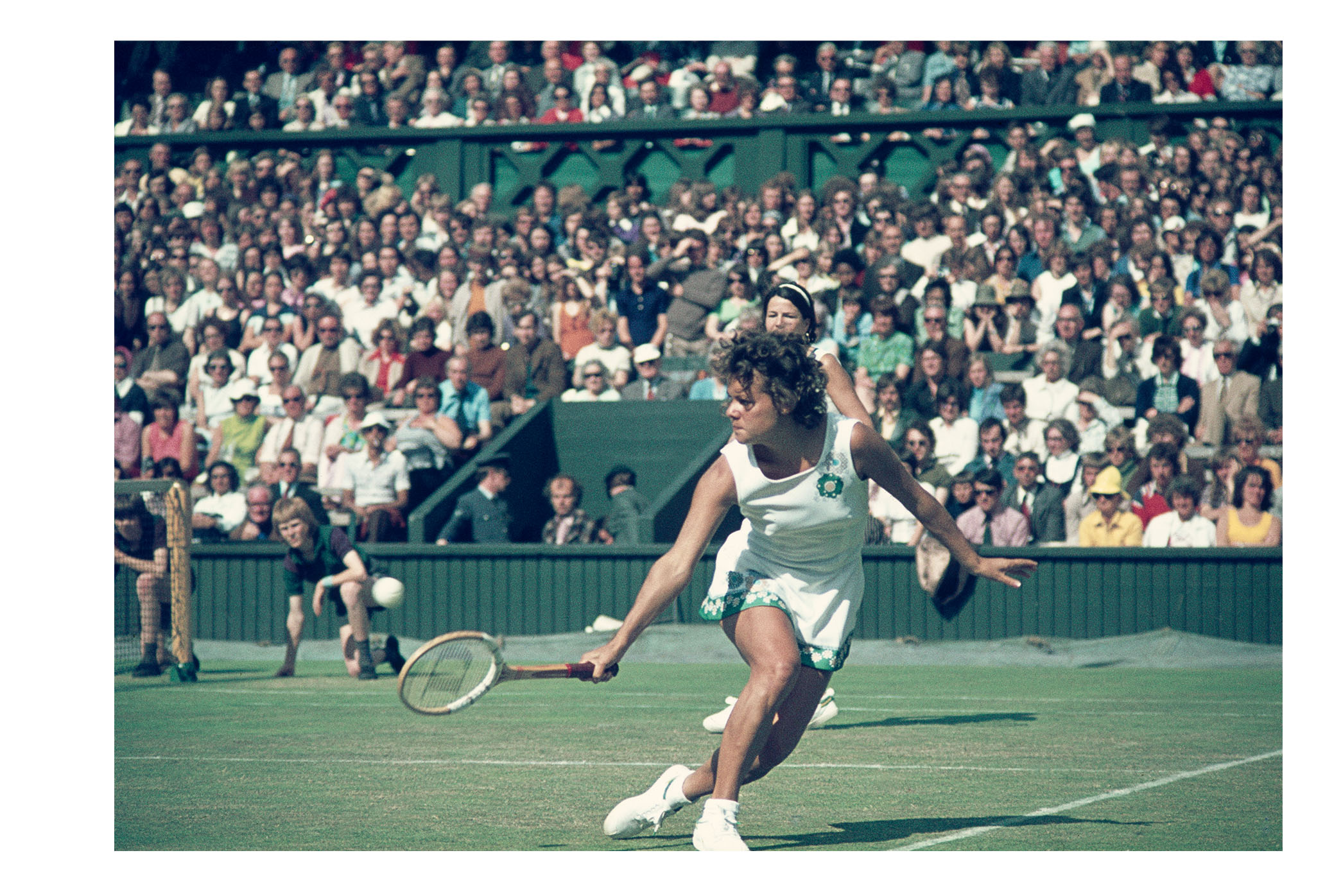

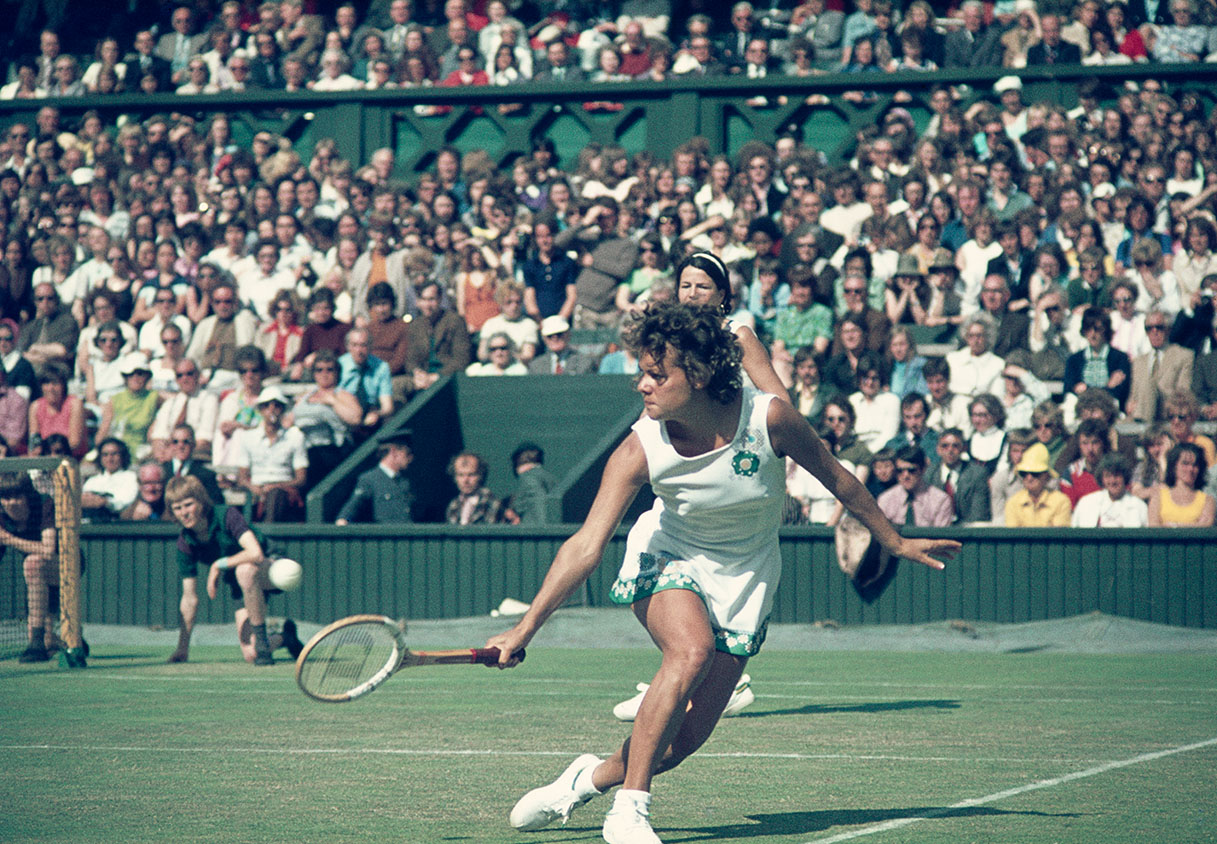

Evonne Goolagong at Wimbledon in 1974, when she won the doubles with Peggy Michel. // Getty

Evonne Goolagong at Wimbledon in 1974, when she won the doubles with Peggy Michel. // Getty

In the wake of Friday’s party, I clicked on the song “Cast Your Fate to the Wind,” then headed 71 years and nearly 10,000 miles southeast from contemporary Wimbledon. The year was 1953, and a 14-year-old boy on a farm in Queensland listened on a transistor radio to the heroics of another Australian teenager, this one from Sydney. The younger lad’s name was Rod Laver, taking in the great deeds of Rosewall, who at the age of 18 won titles that year at both the Australian Championships and Roland-Garros.

These two super-geniuses were present at Friday night’s party; Laver now 85, Rosewall 89. Laver is the four-time Wimbledon champion who also earned two calendar-year Grand Slams. Rosewall is the four-time Wimbledon finalist who ranks with Rafael Nadal and Pete Sampras as the only men to have earned majors in their teens, 20s, and 30s. The Laver-Rosewall rivalry spans hundreds of matches and thousands upon thousands of dazzling sequences and shots.

Though Laver won more often, in their finest battle, Rosewall emerged the victor. It happened in May ’72, at the WCT Finals, a tournament then considered even more prestigious than the current ATP Finals. Held in Dallas, the WCT tournament carried an unprecedented reward of $50,000. It also aired on NBC, at the dawn of tennis receiving significant airtime. Over the course of nearly four hours, with 21 million people watching, the two covered every possible inch of the court and closed out the match in a fifth-set tiebreaker—first man to seven points. With the 33-year-old Laver serving at 5–4, the 37-year-old Rosewall struck two glorious backhands—his signature shot—and extracted a return error from Laver to win the prize.

Friday night, Laver recalled his early teens. “I listened to what Ken was doing and thought, ‘I want to do that,’” he said. As he came of age, Laver modeled his game after Rosewall’s peer Lew Hoad. A few years later, the boy named Rod earned his way onto the traveling Davis Cup squad, where one common task was to squeeze orange juice, and another was to spend 8 to 10 hours a day at work—everything from a long run to five-set practice matches to two-on-one drills, doubles, and, as night fell, a series of sprints.

In his newly published and highly engaging book The Fox, a biography of Harry Hopman, Australian tennis’ head honcho from the ’30s through the ’60s, Aussie journalist Michael Sexton writes, “What they shared was peak physical fitness, an adherence to sportsmanship and a zeal for the contest.”

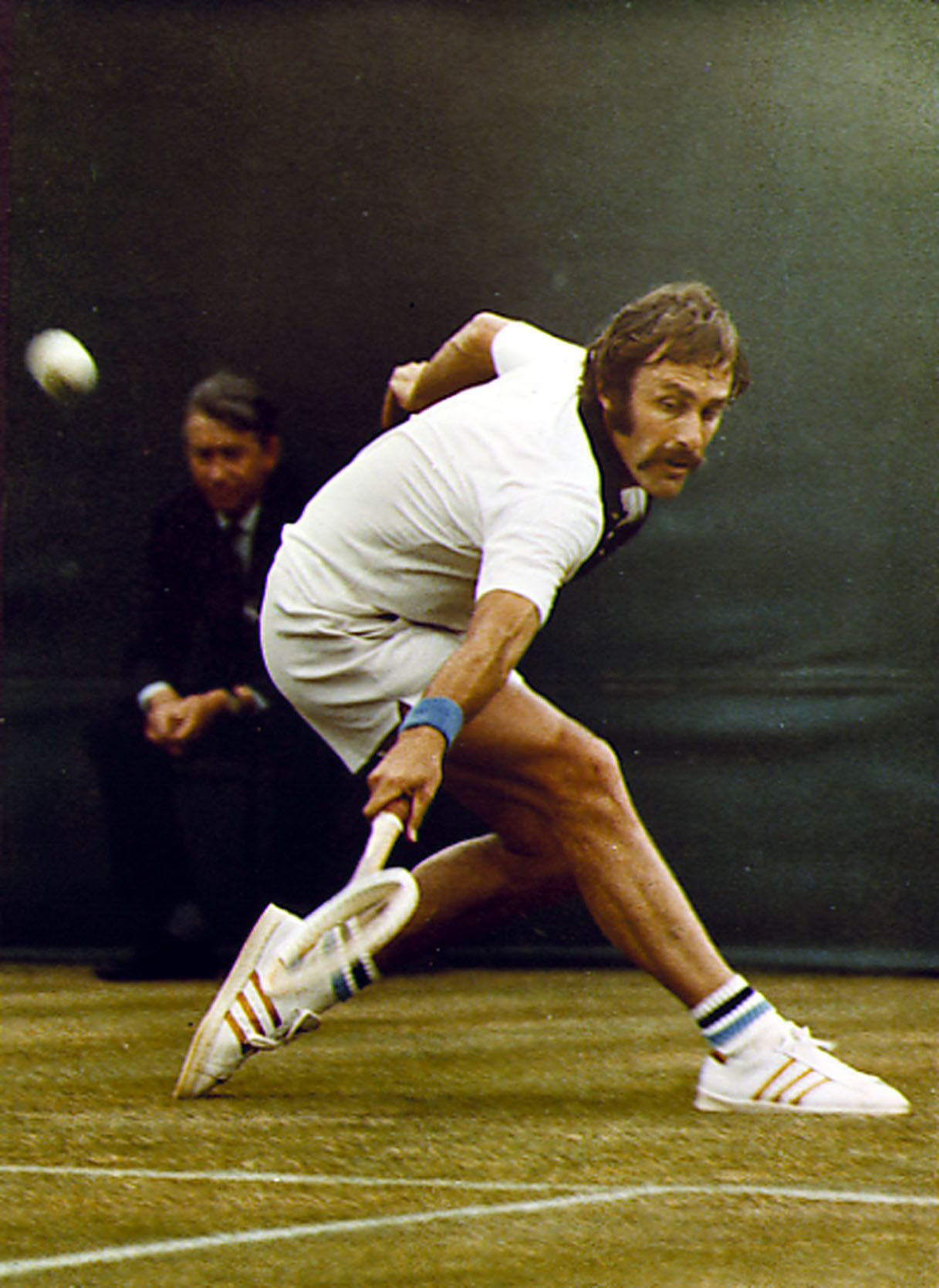

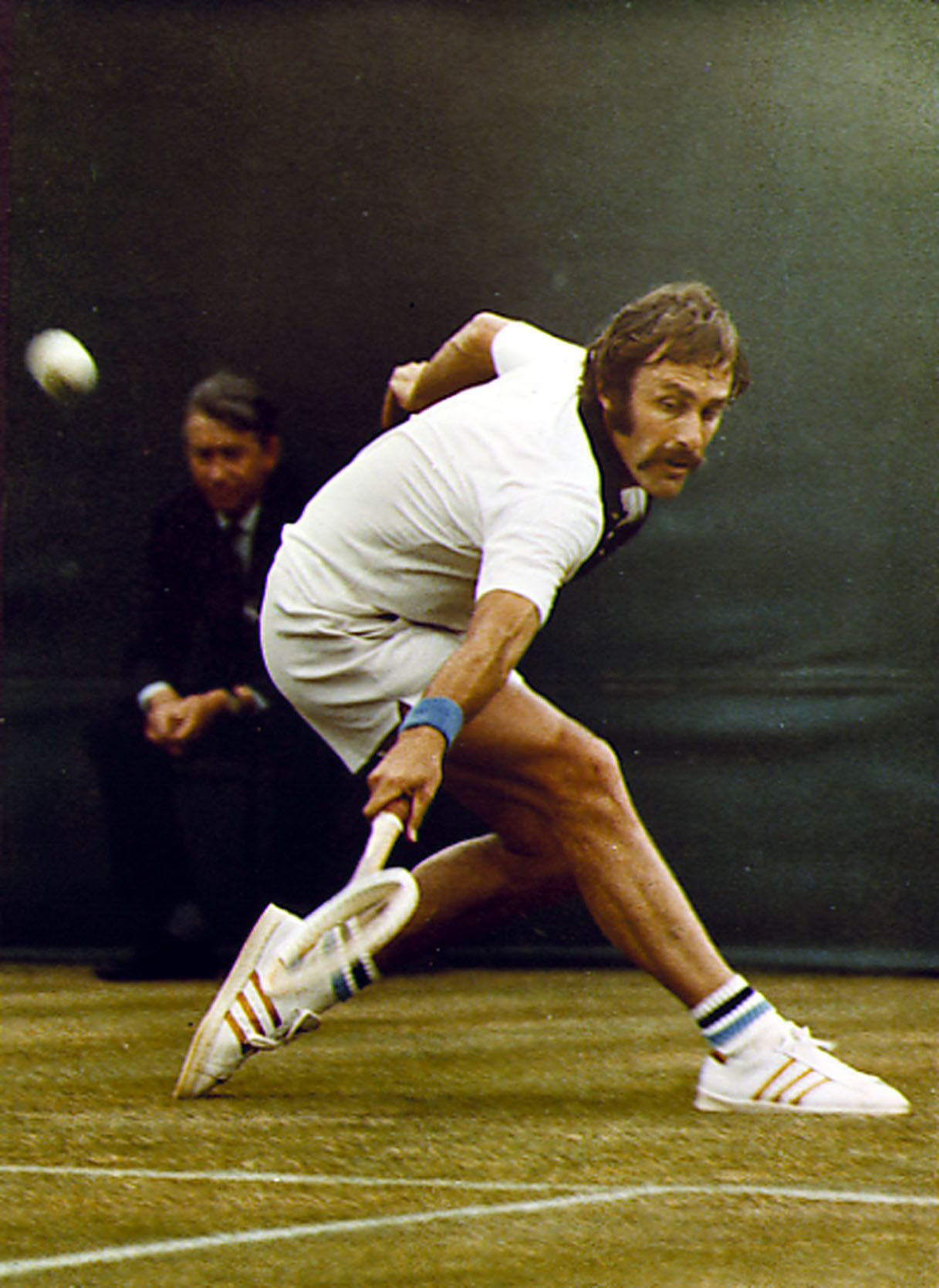

John Newcombe in 1974, the year he won the doubles with Tony Roche for the fifth time. // AP

John Newcombe in 1974, the year he won the doubles with Tony Roche for the fifth time. // AP

Hand in hand with the strong work ethic is the great Australian virtue of camaraderie. Aussies treat tennis as a team sport. Stubbs on Friday evening gave a shout-out to another attendee, Liz Smylie, a four-time Grand Slam champion who’d hit with Rennae when she was a teenager. Those cross-generational connections happen frequently Down Under; all part of Australia’s pursuit of collective glory. “We looked out for each other,” the late Owen Davidson once told me. “We practiced by day and enjoyed ourselves by night. And I’ll tell you this, mate: You’d always have another Aussie there to watch your match.” Based on all this, the case can be made that the Australian devotion to hard work is propelled less by personal ambition and more due to the spirit of friendship and loyalty. Could this nation’s relentless desire to win such events as Davis Cup be fueled most of all by love for one another?

Laver authored a book several years ago titled The Golden Era—that period from 1950 to ’75 when Australia dominated tennis. The legends from that brilliant quarter century are now in their 80s. While their period of on-court excellence has long passed, Australians remain right in the thick of the tennis dialogue. Their national championship, the Australian Open, has over the past 30 years greatly risen in stature, propelled most of all by its superb facility, Melbourne Park, and the arena named for Laver. Thanks to Roger Federer, who for a time was coached by Roche, the Laver Cup has created a unique place for itself in the game’s landscape.

Federer has also spoken about his high regard for Rosewall. For many years Down Under, Rosewall handwrote a note to Federer, wishing him good luck at the Australian Open. Subsequently, Rosewall would leave the missive with the locker room attendant. Asked why he didn’t bring it to Federer personally, Rosewall said, “I wouldn’t want to impose myself on Roger.”

Beyond the understated yet powerful presence of those two titans, Aussies pervade the sport in many other ways. Fitting indeed that a major reason for Jannik Sinner’s ascent has been the addition to his team of an Australian, Darren Cahill. There are also tons of Aussies offering their insights into the world of analysis and storytelling, from announcers like Cahill, Woodforde, Woodbridge, Stubbs, and Louise Plemming to cinematographer Matti Hill, producer Kim Knox, and strategy guru Craig O’Shannessy. Woodforde, Woodbridge, and Stubbs are playing the Wimbledon invitational doubles event, joined by their mates Lleyton Hewitt, Mark Philippoussis, Samantha Stosur, Ashleigh Barty, Casey Dellacqua, and Alicia Molik. An entire crew of print journalists are also at Wimbledon this year, including Australian Tennis magazine editor Vivienne Christie, Tennis Australia writer Leigh Rogers, Melbourne Age writer Marc McGowan, and Fox Sports reporter Courtney Walsh. Even the roguish Nick Kyrgios is giving a go at TV commentary. And let’s also cite long-standing WTA Tour supervisor Pam Whytcross.

The 2024 celebration of those years was of secondary importance to Australia’s deeper tennis footprint and its status as the sport’s torchbearer. Australians can always make news at a tennis tournament. But the story they’ve told for decades runs much deeper than any transitional occurrence. “Literature,” said poet Ezra Pound, “is news that stays news.”

Joel Drucker is happy that he was able to, as the Aussies say, “have a think” about this great nation’s massive tennis legacy.

SIGN UP — YOU'RE ONLY AS GOOD AS YOUR SECOND SERVE.

RECOMMENDED

Postcard from Tennis Paradise

INDIAN WELLS

Clone Wars

PLAYER KITS