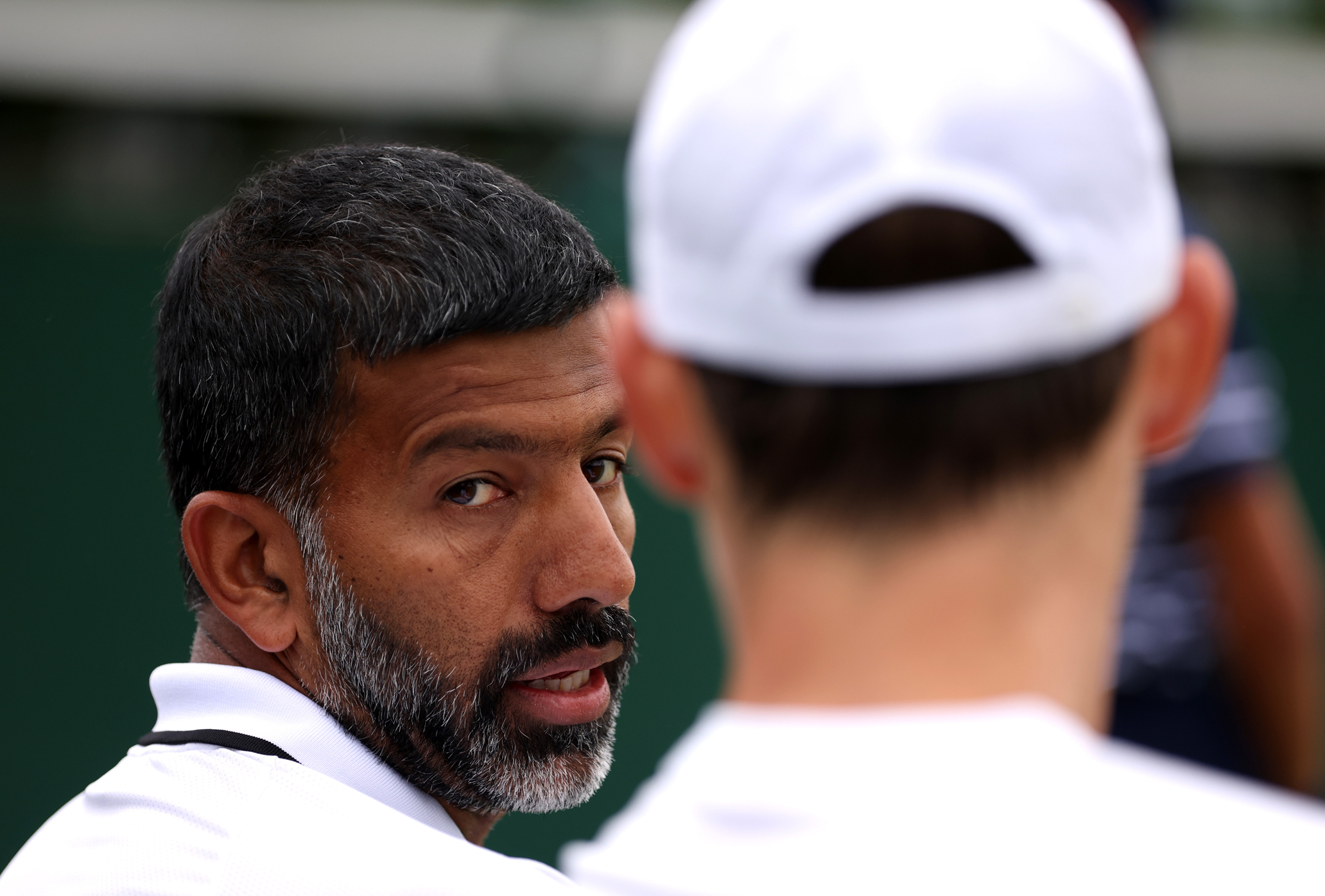

Manna From Bopanna

Manna From Bopanna

The kid from Coorg has been serving up exhilarating pro tennis for over 20 years.

The kid from Coorg has been serving up exhilarating pro tennis for over 20 years.

By Giri NathanPhotography by Clive Brunskill Featured in Volume 1 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

Manna From Bopanna

Manna From Bopanna

The kid from Coorg has been serving up exhilarating pro tennis for over 20 years.

The kid from Coorg has been serving up exhilarating pro tennis for over 20 years.

By Giri NathanPhotography by Clive Brunskill Featured in Volume 1 of OPEN Tennis — BUY

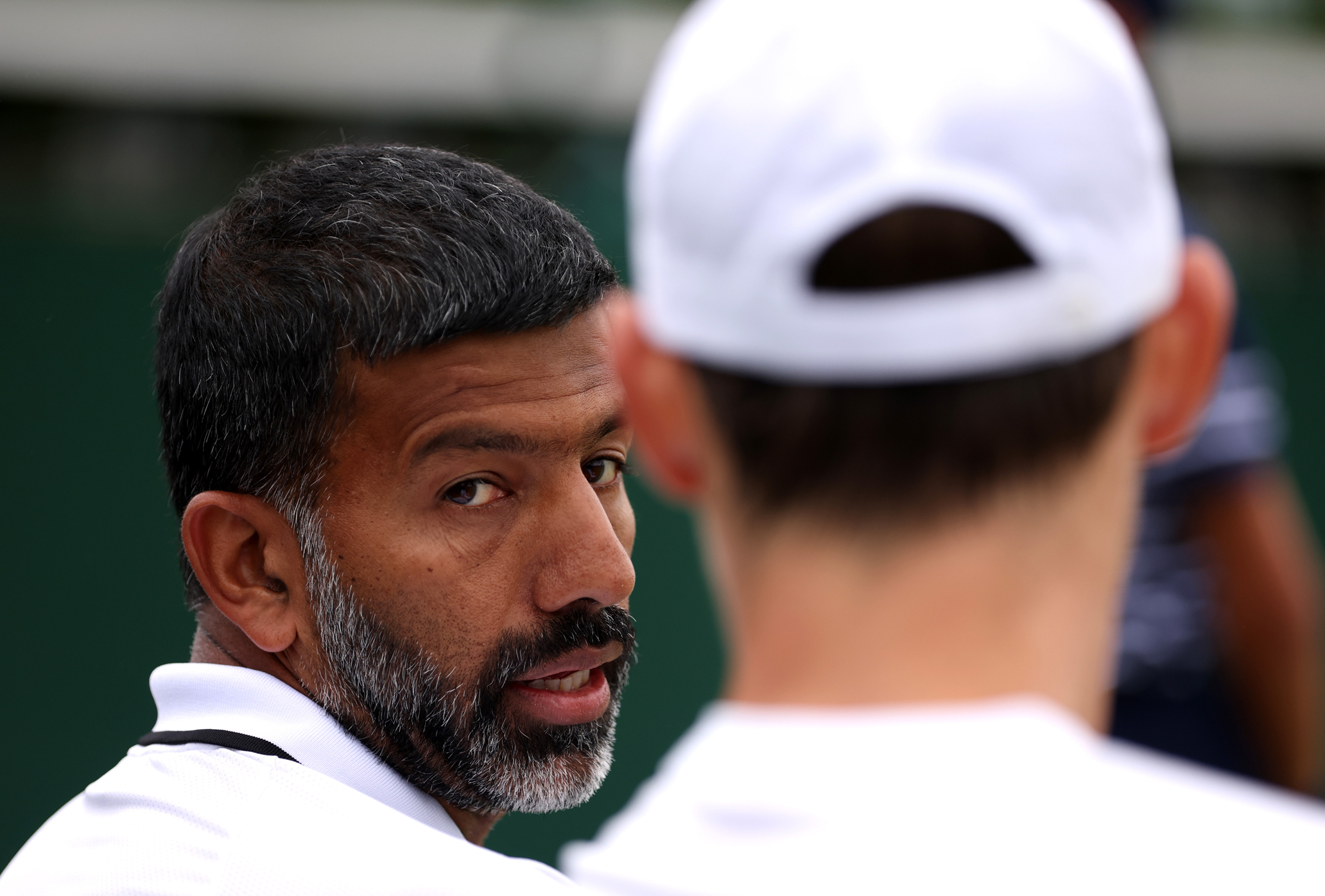

The hair atop the heads of Carlos Alcaraz and Novak Djokovic has been described as “LEGO hair”—low hairline, a dark color, a follicular density so staggering it seems to amount to a continuous surface. Perhaps the part of the human genome that brings about this hair also brings about elite tennis technique. The Indian doubles specialist Rohan Bopanna has this same spectacular hair, though by the time he became world No. 1, it had finally started to thin out at the crown, ceding the ground it had stubbornly held for so long. That’s because Bopanna first became world No. 1 doubles player this past February, at the age of 43 years and 331 days, the oldest man in men’s tennis to climb that particular mountain for the first time. He has achieved the bulk of his most significant career achievements past the age of 35 and has found a way forward with “no cartilage” left in his knees. You wouldn’t know it from the gray-speckled beard, or the gentle stoop in the shoulders that belies the power in his racquet, but Bopanna is a savvy survivor of a punishing game, finding his best tennis in his silver years.

That one fortnight was packed with career milestones, beyond clinching the top ranking. Bopanna logged his 500th win on tour. He won his first Grand Slam title in men’s doubles—the Australian Open, alongside partner Matthew Ebden. And, as a result, he was granted one of India’s highest civilian honors. “The Padma Shri award and being world No. 1 were the two massive recognitions,” he said to me, starting to laugh. “And also it felt like I just arrived on the tennis circuit, even though I’ve been playing for 20-plus years.”

But those countrymen who’ve been tuned in to his every move are awed by his late-blooming brilliance. “To play at this level at 44—there’s only one word for it, and that’s phenomenal,” said Anand Amritraj, who has known Bopanna for decades and captained him for four years on India’s Davis Cup team. “He’s done well for himself, he’s done well for the country, he’s done well in Davis Cup—and now he’s in the Olympics.” Bopanna, making his third appearance at the Games, is the oldest Olympian in the Indian delegation in Paris.

As Bopanna and I speak under the ash-white cloud cover of London in July, a few days ahead of the start of Wimbledon, we circle around a subject of common interest: the odd cultural niche that tennis occupies in India. There’s quite a bit of popular interest, and some rich history, too, spanning from the Amritraj family and Ramesh Krishnan in the ’70s and ’80s, to the Wimbledon-winning Leander Paes–Mahesh Bhupathi duo of the ’90s, to the long run of Sania Mirza in the ’00s and ’10s. But there’s vanishingly little in the way of a national talent development system, and any player who does manage to crack into the top tier of the game is a small miracle, a confluence of irreplicable circumstances. One of Bopanna’s priorities is sharing what he knows, and patching up the broken infrastructure for India’s players of the future, “just so that the journey can be a little bit smoother for them.”

*****

Bopanna spent his early life in Coorg, in the southern state of Karnataka. Stowed on the eastern slopes of the Western Ghat mountain range, it is a psychedelically lush, misty place known for stirring views and extreme biodiversity. It’s also a fine climate for agriculture, and Bopanna was raised on his family coffee farm. Food remains a priority. He tours with his own coffee beans in his luggage; he eats widely in his travels; his young daughter is consequently developing an expensive salmon sashimi habit. He recommends me some Coorg specialties for my next visit: Akki roti, a soft flatbread of rice flour flecked with onions and chilis, goes well with pandi curry, a darkly spiced pork dish shot through with a bracing vinegar made from the gummi-gutta fruit. Childhood in Coorg was defined by nature and exploration. When he wanted a glass of milk, he went straight to the cow. Dinner came out of the vegetable garden. Whenever snakes got inside the house, his mom would dispel them, while his dad just ran away. Young Rohan was covered in a permanent coat of scrapes and bruises from biking and climbing trees all over the coffee estate. Looking back at his birthplace, Bopanna gives credit to the region’s unique cultural microclimate within a country that is broadly indifferent to the serious pursuit of athletics. “In Coorg, 80 or 90 percent of the population introduced sports to their kids. It is a very different culture,” he said. “Going through a sports journey or going to the army are the two fields that are very, very encouraged in Coorg.”

Which is not to say it was a natural environment to learn tennis, specifically. But the tennis bug had already taken hold of the family. Bopanna’s parents went to England for their honeymoon in 1975. While in London, his dad and a friend insisted on investigating what exactly was going on at Wimbledon. They showed up on site with little prior knowledge, grabbed grounds tickets from departing fans, were let into Centre Court by an accommodating usher, and were told they could watch from the stairs for as long as they wanted. They stood there for hours. Upon return to Coorg, Bopanna’s father and his friends built their own tennis club and, alongside their wives, taught themselves how to play the game. Rohan joined in at age 10, playing before school early in the mornings because club members would get priority later in the day. Early instruction: whatever his dad could glean from books, which meant Rohan learned to hit his forehand, backhand, serve, and volleys all with the continental grip, and he’d only catch up with contemporary tennis ideology years later. Early nutritional plan: mom’s intuition and an abundance of homegrown food. Early fitness: a hammer, some logs to hit with the hammer, some poles and ropes that dad set up. To this day, there is no gym in the area. Tennis balls were whatever the club happened to be able to afford. When a string broke, someone would have to bring the racquet for a restring in Mysore (a two-and-a-half-hour drive in present traffic) or Bangalore (closer to five hours).

Even within a sport full of unusual journeys, a Coorg coffee farm is a faintly preposterous place to cultivate a Grand Slam champion. “It’s not like there was any place to go and train, or to find out what it is,” he said. “There was no internet back then. We didn’t have electricity, forget internet. There were many times in school, I was studying under candle. But this was a normal thing for anybody growing up from a small village.” Bopanna was alone on the coffee estate most of the time; while most of his friends had been sent off to boarding school, his dad wanted to keep him close to keep developing his tennis. That often required serious improvisation. Once, when he was desperate to prepare for a tournament during monsoon season, a coffee drying yard was repurposed into a tennis court, with ropes laid down as lines. These experiences seem to have left him in a state of reverse jadedness, a kind of long-release appreciation for all the places tennis has taken him. “Every time I come to these events,” he said, gesturing from a perch above that same court where his dad once stood rapt on the stairs, “I really feel that I appreciate it more.”

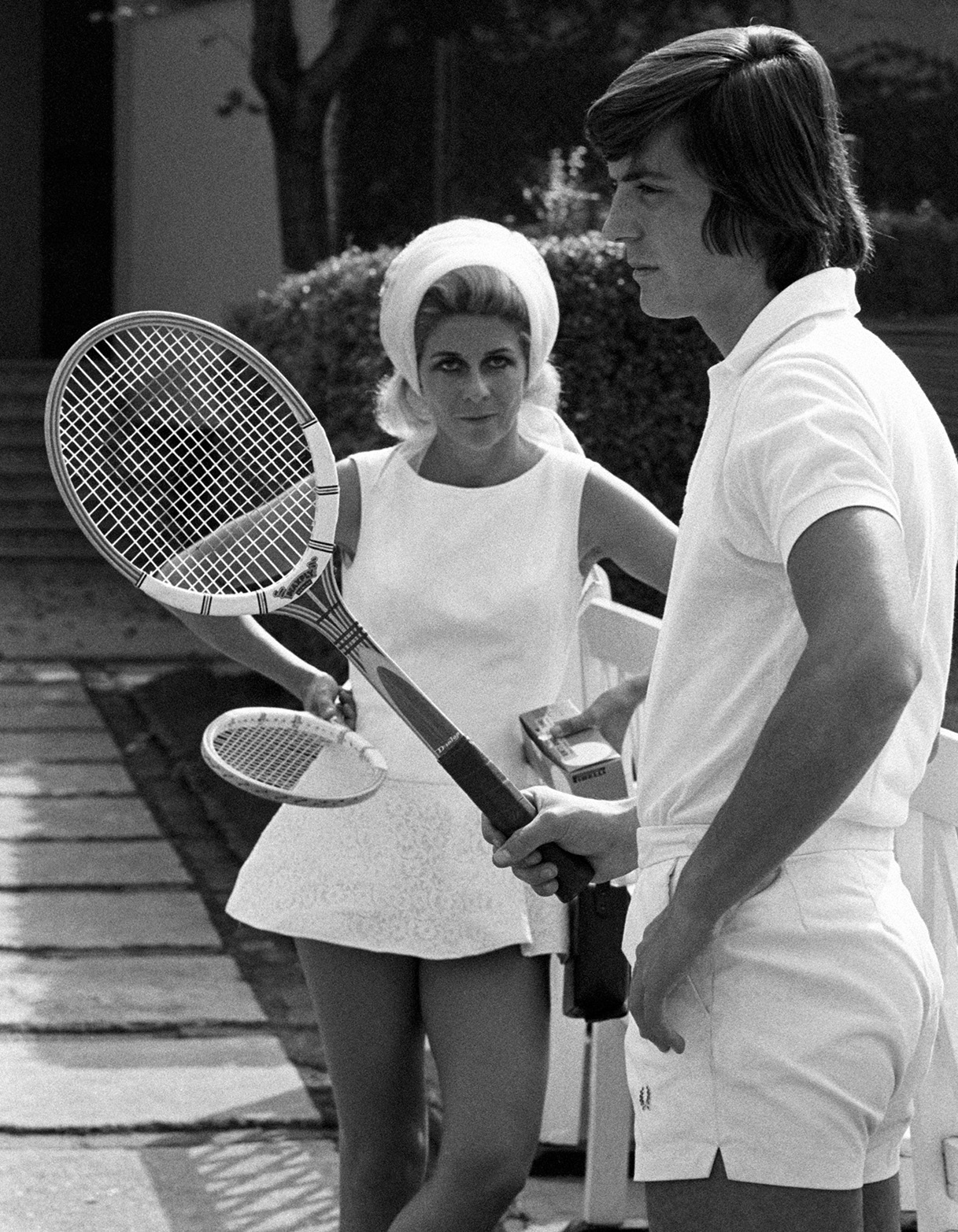

“Gorgeous” Gussie Moran, tennis’ first pinup. // Getty

Lea Pericoli with Italian tennis icon Adriano Panatta // Getty

Eventually Rohan’s tennis ambitions outgrew Coorg, however. At age 11 or 12, he tried to enroll in tennis academies and was told he was not good enough. By age 14, an academy in Pune, Maharashtra, said they wouldn’t offer him a scholarship, but they would let him enroll on full tuition. “For me, it was like freedom. Being at home with strict parents, I thought, ‘Oh, this is great. I’ll be getting some more free time,’” he said. The reality turned out far grimmer: He stayed in a hostel with a warden and woke up at 5 a.m. every day to make it to fitness at 5:45. Any student who missed a fitness session could not play tennis that day. He often found himself biking 14 or 15 kilometers a day, sometimes through cold and rain, just to get between the different training locations, an experience that would eventually inspire his own “all under one roof” philosophy of tennis instruction, so that the tennis pupils of the future don’t find themselves rain-soaked at dawn.

Once Bopanna broke into the pros, he played some singles but found real traction on the doubles court, the site of most Indian tennis success over the past three decades. Early in his career he thrived alongside the Pakistani player Aisam-Ul-Haq Qureshi, a partnership known as “the Indo-Pak Express,” a small bridge across a geopolitical abyss. Together they won five ATP titles and made the final of the 2010 US Open. Bopanna won his first major title at the 2017 French Open, a mixed-doubles trophy alongside the Canadian player Gaby Dabrowski. But by 2019, pain was interjecting in his career. His knees were devoid of cartilage, and he didn’t want knee replacements. Hyaluronic acid injections did nothing. After receiving platelet-rich plasma injections, he was told he’d only really notice the effects after strengthening his legs, but he was in too much pain to try traditional gym workouts like squats or leg extensions. A cousin suggested Iyengar yoga, a style that emphasizes ultraprecise body alignment and long static poses. Bopanna, not much of a practitioner, called The Practice Room, an Iyengar center near his home in Bangalore, and laid out his woes. While they’d never before worked with an active athlete, he was soon coming in for 90-minute sessions. After helping him rebuild the strength in his legs, they also got to work aligning his back and shoulders, too.

Asked about his favorite poses, Bopanna smiled. “I don’t think there’s a favorite, because there are some positions where I know they’re good for me, but you have a high tolerance of pain, because they put me in for seven, eight minutes tied with ropes and weights, just lying down there. And now I think they know I can take a good amount of pain in the body, so they’re also pushing me to every limit. But after the class, it just feels incredible.” These excursions into voluntary, restorative pain have allowed him to play his sport free of any pain, which was an unimaginable prospect just a few years prior. He used to take two or three painkillers a day and has now quit them altogether. Bopanna said he’d love to travel with his two yoga instructors, but costs already pile up with a physio and coach. So he developed a new strategy. Wherever he’s staying on tour, he takes photos of the layout and furniture, sends it to his instructors, and they devise exercises that make use of the props on hand. Suddenly he rapped the wooden surface in between us: “This table we’re sitting on can be a great prop for yoga, because it has sharp edges.”

*****

Any 20-plus-year career has its ups and downs, and not long after these significant physical revelations, Bopanna found himself back in the dumps. A few months into 2021, he considered abandoning the racquet for good. After a loss in Estoril, Portugal—his seventh loss in seven matches played that season, winning only one set along the way—he found himself sitting by the ocean, wondering what it was all for. “What am I even doing? I’m not even winning matches, I have a family at home. Should I just call it a day and just go back?” he recalled thinking at the time. His daughter was 4 years old. He could easily throw himself into the third-generation coffee business. But he kept at tennis, trying to restore whatever joy he could, and picked up three titles in 2023. The next year he landed in arguably the most fruitful partnership of his career. Bopanna has described a doubles partnership as a marriage, and on that analogy, it is never too late for love. Matthew Ebden, a 36-year-old Australian veteran, completes him. Pooling together their tennis histories, they realized they’d experienced most of the tour: “No matter which tournament or which round we were in, we had already been there before,” Bopanna said. They won the Australian Open title this year and have also picked up titles in Indian Wells, Miami, and Doha. Bopanna thinks Ebden’s brilliant returns and consistency complement his own power-oriented game, defined by a big serve and forehand.

Part of Bopanna’s longevity can be explained by how doubles strategy has slowly evolved in alignment with his own shifting skill set. Earlier in his career, Bopanna, like everyone else, was a big practitioner of the serve-and-volley. Not so much these days, because while his knees have improved a great deal, they’re still not too happy about those speedy advances to the net. Fortunately, that’s not as big a part of his job description anymore. When I talk to Anand Amritraj, the former Davis Cup captain, he marvels at how much doubles has transformed since his heyday, when he was in the 1976 Wimbledon men’s doubles semifinal with his brother Vijay. “Rohan serves and stays back—but he’s got that massive first and an equally massive second serve,” he said. “So he’s able to do what he does; he stays back and whales on forehands. And the two returners are in the backcourt, they’re not chipping and charging, like a Paul Annacone.” The image of three players at the baseline and only one at the net might be anathema to an Amritraj, but it has served Bopanna’s tennis neatly, well into his 40s. So has his new attitude toward scheduling. Earlier in his career, he insisted on playing as many tournaments as possible, but he has learned to devote the off weeks to recovery and preparation, maximizing the events he does play.

*****

Bopanna is eager to distill all his gradually accumulated wisdom for India’s next cohort of players. Gesturing around the grounds, he somberly observed that there are no Indian players in the qualifying draw at Wimbledon. “Everybody just talks about 1.5 billion people, why don’t we have some? You will not have some if nothing is there to give that direction to help somebody,” he said. He’s seen a lot of great junior talent opt for the American college route and never circle back to tennis. While he considers the overall sporting culture in India to be lagging 30 or 40 years beyond the U.S. or Europe, he points to cricket and badminton as sports with a robust national support system. Tennis isn’t one of them. With his academy in Bangalore, Bopanna has tried to outline his ideal tennis pedagogy, and crucially, it does not involve lengthy bike rides from point A to point B. Everything is centralized: coaching, fitness, lodging, food, and quality education—a sticking point for many Indian parents, he said. Bopanna also wants to incorporate yoga in his programming, as he believes it’s better adopted early than after the ravages of a tennis career. He sponsors underprivileged students. He wants to improve access to quality coaching at a young age, and he wants to create more opportunities for Indians to get exposure to high-level competition without prohibitively expensive travel. To that end, Bopanna dreams of a Futures and Challengers tournament in every state of the country. If anything, India has only lost ground here in recent years. In the 2024 season, neither the ATP or WTA will hold any tour-level events in the country; as for the lower-tier events, there are nine on the men’s side and six on the women’s side.

Building out these tournaments, he hopes, would improve the overall status of the sport in a cricket-centric country. Bopanna, as mellow and good-natured a professional athlete as I’ve ever met, seemed slightly amused by an abrupt rush of national appreciation for a career that had already seen significant successes over two decades. “I think that the challenge is that nobody really understands tennis,” he said. “Say both of us are playing an event, right? You come back and you say you got a silver medal. I come back and I say, ‘I’m runner-up.’ You go to a layman, and the guy’s just going to relate to silver.” Tennis’ many tiers, and all its specific nomenclature, can confound even a sympathetic outsider. “I may have 25 titles…but the 25 gold medals are valued more in the country than 225 titles, right?”

The sport doesn’t make it easy, either. It often feels impossible for him to view his own matches at an ATP 250, Bopanna observes. But badminton’s standing has shot up in recent years due to increased coverage, and he thinks tennis can follow suit. “It’s something which just will change only with the sport being more telecasted or spoken about in the country—and automatically, they will understand what I am doing, what Sumit is doing,” he said, referencing Sumit Nagal, the talented singles player, ranked No. 80 at time of writing, who famously had 900 euros in his bank account late last year before stringing together some career-sustaining wins at the start of 2024. Bopanna says he’s talking to entrepreneurs to try to secure the funding needed to transform India’s talent development pipeline into something closer to Italy’s, the system he admires most. Perhaps, with his sustained effort, an Indian career in tennis won’t have to feel as solitary and perilous as it has in the past. But for now, the yoga poses and ice baths are still working, and he’s got a few more seasons to grace the doubles courts before he shifts his full energies to coaching and coffee beans.