Short Skirts and a Long Life

Short Skirts and a Long Life

Italian tennis icon Lea Pericoli was known for the flamboyant fashions and gender politics of a bygone era.

Italian tennis icon Lea Pericoli was known for the flamboyant fashions and gender politics of a bygone era.

By Ben RothenbergOctober 18, 2024

Short Skirts and a Long Life

Short Skirts and a Long Life

Italian tennis icon Lea Pericoli was known for the flamboyant fashions and gender politics of a bygone era.

Italian tennis icon Lea Pericoli was known for the flamboyant fashions and gender politics of a bygone era.

By Ben RothenbergOctober 18, 2024

Lea Pericoli in a classic Ted Tinling confection. // Getty

Lea Pericoli in a classic Ted Tinling confection. // Getty

When I got the chance to interview Lea Pericoli five years ago, it felt entirely appropriate that we met in Rome. She’d been Italy’s best women’s tennis player from the late 1950s to the mid-1970s, after all, and sprinkled her perfect English with enthusiastic assents of “Si, bravo” anytime she agreed with what you were saying.

But perhaps more than just Rome, it was fitting that I met Lea Pericoli within walking distance of the Vatican. Because Lea Pericoli was an icon, and by the time I met her, many would describe her as a relic of a controversial historical force. But I thought of Lea Pericoli more like a patron saint: a guardian and vessel of a certain moment in tennis history and certain values, now perhaps considered retrograde or regrettable. She was the archetype of a time when women realized they had to dress for a show to be seen.

“A forehand or a backhand don’t get spoiled if you have a pretty dress,” Pericoli told me. “You don’t spoil the game. You just make it a little more pleasant.”

Decades before Billie Jean King would prove that women’s professional sports were a viable concept, only a handful of women were given opportunities to earn money playing sports, and it wasn’t necessarily because they were the best players.

The most lucrative draw in women’s tennis in the early 1950s was Gertrude “Gorgeous Gussie” Moran, a Californian who was on the fringe of the top 10. Moran became a postwar pinup after her appearance at Wimbledon in 1949, when she wore lace-trimmed knickers designed by tennis couturier Ted Tinling.

At buttoned-up Wimbledon, All England Club officials decried Moran for “bringing vulgarity and sin into tennis.” But Moran’s photos went viral, as we’d say now, splashed across front pages around England, America, and the world.

As reported by Time in November 1950: “Gussie Moran got top billing as the tennis pros opened their winter tour in Manhattan’s Madison Square Garden last week…. [As] a reflection of tennis ability this made no sense, but the pros knew what they were doing.” As top draw, Moran took home 30 percent of the gate at Madison Square Garden.

_________

It was this world, where athleticism and traditional notions of femininity were often considered antithetical, into which Lea Pericoli ascended a few years later. “Sport doesn’t flatter so much a woman,” she told me. “So, you must try to keep being feminine.”

Pericoli’s ethos was just what the male-dominated tennis world was looking for. When the Italian federation sponsored Pericoli to compete at Wimbledon for the first time in 1955, she’d already caused a pretournament stir with her appearance at a warm-up event in Beckenham, getting on the front pages of many British newspapers for her outfit alone, dubbed “Luscious Lea” and “The Lollobrigida of Tennis.” Eager to join forces with this new sensation, Tinling offered to outfit Pericoli for Wimbledon. “It is a great honor, because Tinling only dresses the greatest and most beautiful,” Pericoli later wrote.

Pericoli took court for her first match at Wimbledon decked out in a Tinling creation: a short dress with the shock of a Schiaparelli-pink petticoat underneath, flouting Wimbledon’s strict all-white rules. Photographers scrambled to Court No. 4 to snap photos of her, often lying down to achieve their desired up-skirt angles.

“Gorgeous” Gussie Moran, tennis’ first pinup. // Getty

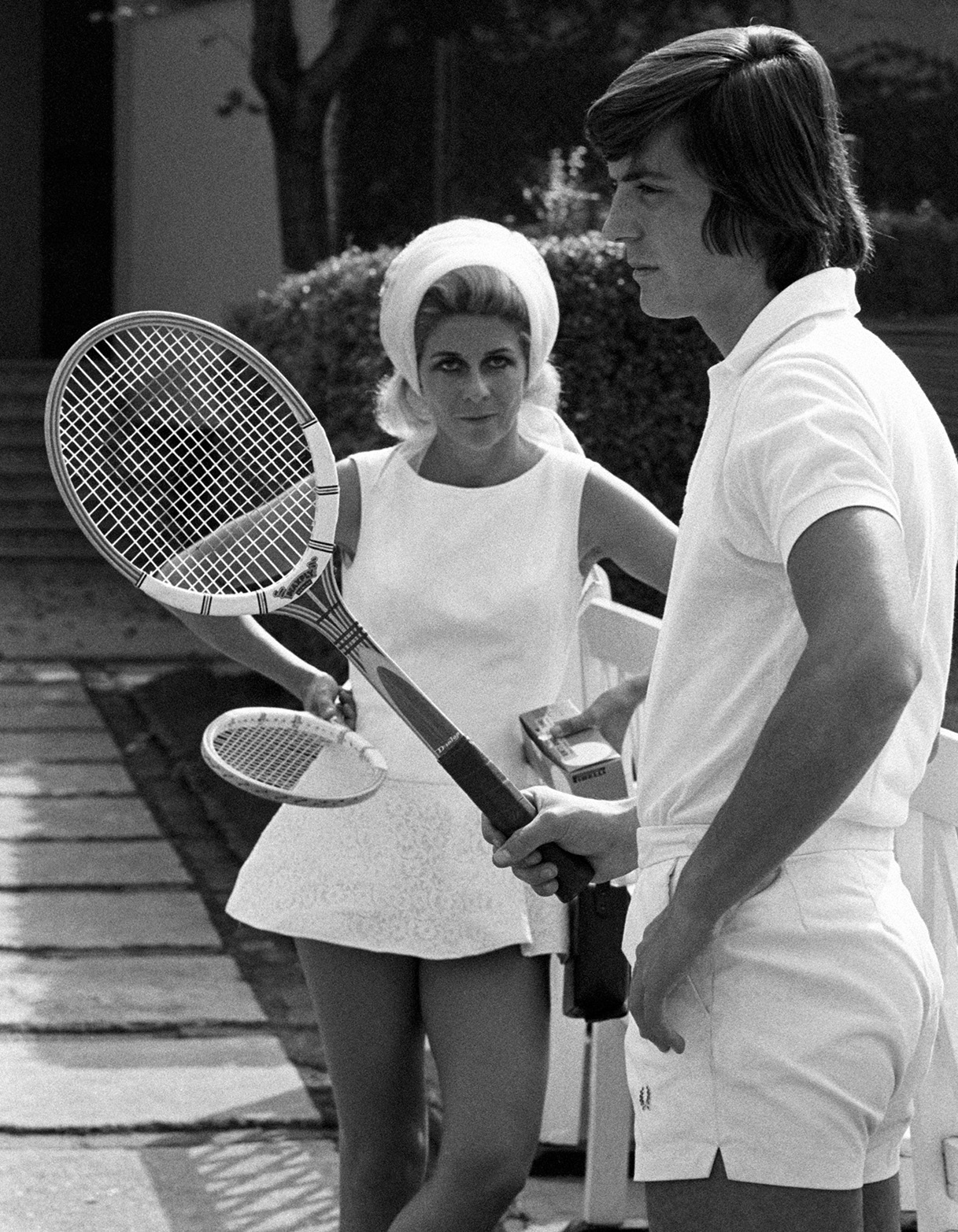

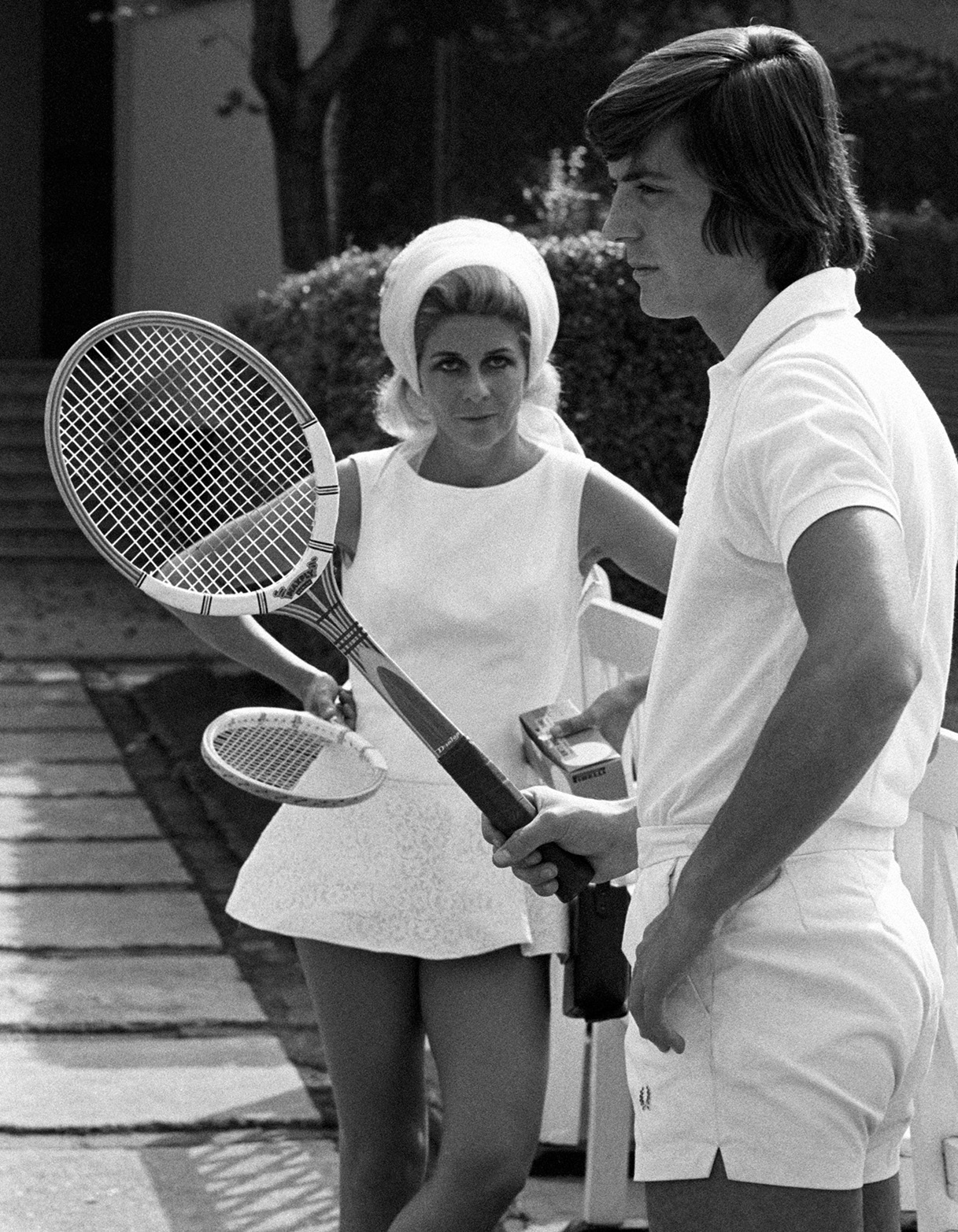

Lea Pericoli with Italian tennis icon Adriano Panatta // Getty

“Gorgeous” Gussie Moran, tennis’ first pinup. // Getty

Lea Pericoli with Italian tennis icon Adriano Panatta // Getty

“I go out onto the court and all hell breaks loose,” Pericoli recalled. “I have about 20 photographers lying under me. Every move I make causes an infinite series of clicks.”

The circus-like atmosphere unnerved Pericoli, and she lost in three sets. But because of what she’d worn, she was the biggest story at Wimbledon that week. The Daily Herald gushed that Pericoli “lost her contest but found her place in public memory as this year’s femme fatale of fancy-pants…. [The] match is ended, but the lingerie lingers on.”

Pericoli was initially mortified by how much attention she had attracted. “I lost the match, I was in tears,” she told me. “My father forbade me to play tennis because he was shocked about all the first pages and so on.” So when she returned to court for her doubles match later that week, Pericoli wore a conservative top and pair of shorts from the British brand Fred Perry to deflect any further spotlight. The abandonment of his work infuriated Tinling, who refused to work with her again for years.

But after the waves she’d made, promoters around the world saw how Pericoli was being covered as “the biggest sensation Wimbledon has seen since Gussie Moran” and began offering her spots in their events. “I wasn’t the strongest player in the world, but with that, I got really wonderful invitations all over the world,” Pericoli told me. “I went to the Caribbean and I went around South America. Just for that. Not so much for my tennis.”

Pericoli “made peace” with Tinling and came to embrace her power as his on-court mannequin, model, and muse. Tinling continued pushing the envelope with Pericoli, and she traveled alongside him to new markets where he hoped to sell his creations, embracing his sense of camp. On a trip to South Africa, for example, Tinling made a gold dress and pair of diamond-studded panties for Pericoli to wear as an homage to the country’s mining industries.

Pericoli assured me that the ostentatious outfits weren’t cumbersome. But sometimes they required mindfulness: Wearing a skirt made of 300 ostrich feathers, as she did once at Wimbledon, meant that you had to wipe a sweaty hand elsewhere, lest you ruffle and muss the delicate design.

Whether it was modeling for Princess Grace Kelly in Monaco or a group of English women at a garden party, Pericoli and Tinling delighted in dazzling their audiences. “I have a little mink skirt, a skirt of swan feathers, a dress made of rose petals, another made of bunches of lily of the valley,” Pericoli wrote in her 1976 memoir Questa Bellissima Vita. “Fringes, sequins, veils. Let’s say that my tailor and I have lost our minds a little. But this will serve to revolutionize clothing in the world of tennis.”

Pericoli was also prudent about what she put on, only wearing her boldest outfits when she believed victory was assured.

“You must be a little careful, because if you go out there with feathers, and you lose, you’re dead because the press will kill you—they will pluck you like a chicken,” she told me. “I always was intelligent enough; I used to know up to what level to dare. When I knew I was going to lose, I just wore a nice little white dress.”

Pericoli and I spoke of two revolutions that followed her in women’s tennis. The first was that previously conservative women’s tennis players began to dress more like her, wearing short skirts or dresses with visible frilly underwear underneath, often designed by Tinling.

Billie Jean King, an advocate for substance over style but also a realist about how to draw eyeballs for her nascent women’s tour, wore many of Tinling’s creations during her career, including during her win over Bobby Riggs in the 1973 Battle of the Sexes.

“Fashion really reflects where women were, and the lack of freedom we had with our bodies and with sports, how restrictive society was for women through fashion,” King told me a few years ago. “Fashion tells you where people are, how things loosened up over time.”

The second revolution we discussed was the one led by King—whom Pericoli was proud to mention she had once beaten on a clay court in Gstaad in 1969—to make women’s tennis a viable, and eventually hugely lucrative, career opportunity.

“I think it’s amazing,” Pericoli told me as we discussed the many millionaire players in the modern women’s game. “And I’m very glad for them because I never would have thought in my life that a miracle like this would have happened…. Billie managed to lead this kind of rebellion.”

As we sat in a small garden at the Foro Italico between courts Pietrangeli and Centrale, though, Pericoli made clear, perhaps unsurprisingly given her earlier generation, that she didn’t cosign everything King had stood for. “I’ve never been—come si dice—a feminist,” she told me.

By leaning into her ability to draw attention for her outfits, Pericoli had worked within the patriarchy rather than against it. “Now I think it’s even too exaggerated, you know, to have the same kind of prize money,” she told me. “I will be very unpopular with this, but I don’t think that in the world we are living now, in this time, that women can complain…. I don’t want to be like a man. I don’t want equality…. That’s why I don’t like women liberation, you know. Very dangerous. Very dangerous. You mustn’t have an enemy when you see a man.”

_________

Though she never reached a major quarterfinal in singles, Pericoli kept playing into her 40s, even after battling cancer. From the 1980s through the 2010s, she served as a master of ceremonies at the Foro Italico. She also worked for a Milanese newspaper, writing about tennis and fashion.

Pericoli remained ready to be seen at tennis courts throughout her life. She was formally made an ambassador for women’s tennis by the Federation of Italian Tennis (FIT) in 2004, and her platinum coiffure was unmissable in her front-row seat of Court Centrale. She put in long hours watching tennis in the sun well into her 80s. “Because it would be horrible to have a front-row seat and not to be sitting there,” Pericoli told me. “At least for politeness. It’s a big pleasure, but also a little duty that you must show respect, you know?”

The respect was reciprocated by the tournament: In 2018, the Foro Italico opened a new on-site restaurant, with walls painted bright pink, named “Lea” in her honor.

When we met in 2019, during a brief respite from her front seat, Pericoli wore a crisp white pantsuit and Tiffany & Co. glasses. She was 84 but still nimble and still sharp in her second language. “My life is fantastic,” she told me. “I like this role of being an ambassador for Italian tennis, and I enjoy life. It’s wonderful. The only shame is that it will end, unfortunately. I would like for it to be a little longer, for my taste.”

Lea Pericoli, with short skirts and a long life, passed away on Oct. 4, 2024. She was 89.

Vintage Pericoli. // Getty

Vintage Pericoli. // Getty