Stallions Only

Stallions Only

Matteo Berrettini and Jannik Sinner bring Week 2 energy to the second round.

Matteo Berrettini and Jannik Sinner bring Week 2 energy to the second round.

By Giri NathanJuly 4, 2024

Sinner striking. // Craig E. Shapiro

Sinner striking. // Craig E. Shapiro

Wednesday night at Wimbledon the press box on Centre Court was densely, vibrantly Italian. That was only right: Matteo Berrettini and Jannik Sinner stood on the grass before us, a contest so promising that you wish it was taking place deep into week 2. But this was just a second-round match, since Berrettini, the finalist here three years ago, is still working his way up into the top 50 after some loss of form and a six-month injury layoff. That meant that he wasn’t present in the office to witness his countryman’s rather abrupt transformation into the top player in the world. “At the end of last year I was injured and I wasn’t on tour to see him live with my eyes. And then I had the chance to go to the Davis Cup and it was unbelievable,” Berrettini said earlier this week. “It was like we were looking at each other saying, ‘Is this guy real?’ Because he wasn’t missing. Hitting every ball full power.”

At that Davis Cup, Sinner led Italy to the title, dispatching Novak Djokovic for the second time in a two-week span, and then he more or less sustained that rampage until the present day. He’s gone 38–3 since that moment, and now the 28-year-old Berrettini is the one drawing inspiration from the man six years his junior: “Personally, it gives me so much energy to just try to be there and to play against him and to be at his level. For me, it’s really useful.” On Wednesday, he spent the better part of four hours staying right on Sinner’s level, enforcing his own brand of heavyweight tennis and losing only by the tiniest of tiebreak margins, 7–6(3), 7–6(4), 2–6, 7–6(4), a Berrettini-on-grass scoreline if I’ve ever seen one. The tail end of every set always turned up to brilliance; the crowd was often lured onto its feet by the sheer quality; the Italian press corps was chirping, pontificating, and lightly admonishing one another not to openly cheer for the elder underdog Matteo Berrettini. In the end the top seed kept hacking his way through what projects to be a vicious Wimbledon draw.

Over my first watch of Berrettini on grass in person, his history of success on this surface became more legible to me. Even the parts I already understood on paper. It’s one thing to read 129 mph on your TV screen, and it’s another to see it just slide irretrievably off the turf, past a brilliant returner who has even guessed correctly. I was most struck by his court sense and comfort using the attributes of a grass court to his advantage. Sinner’s game plan was obvious from the get-to, and it’s not an uncommon one against this particular opponent: Take the pain to Berrettini’s backhand side, since his stiff two-handed backhand is a ghost of his potent forehand. But the big man compensates that with a backhand slice I knew to be effective but didn’t fully appreciate until I saw, up close, how accurately he places it, how its slow movement through the air buys him some time to recover in rallies, and how it barely bounces off the grass. It’s one of the finest slices on tour, and Sinner tested it with his endless backhand crosses—a match-long cross-examination that rarely elicited a flinch. In the rally of the match, he sent one slice around the net post that had me hooting. Berrettini even liked to cheat his court position over to the ad side, shrinking the possible space where Sinner could find his backhand and daring Sinner to take his backhand down the line, which he shied away from for much of the match, perhaps because of how difficult it was to lift that low slice up and over the net and into the court. Berrettini throws big punches, but it’s that defense and craft that keep him alive in these contests against better players.

Even as Berrettini approached his old grass-court glory, Sinner steadily revealed the extra substance in his game, seen most clearly in the tiebreaks, where he was better equipped to win any given point on either side of the ball. Sinner is so balanced, so consistent a threat in every moment, on both wings. While Berrettini came away with four breaks of serve compared with Sinner’s two, that’s slightly misleading, because it was the world No. 1 who placed more pressure on return throughout the contest, winning 59 points on return to Berrettini’s 38. I loved watching him bob and weave around the Berrettini service bombs. One second he’d be throwing his gangly limbs out of the way of a body serve, the next he’d be blanketing a second serve with perfectly grooved timing. He tinkered a little with his setup, and I asked him afterward how he thinks about return positioning when playing a server as good as his friend Matteo. He said that the way the ball slips off grass makes it hard to get too experimental with positioning, but he tried to mix it up on second serves. “It’s also a little bit a gut feeling, no? Which can help you, and you just have to go for it.” In a match against Berrettini, you might just have to have the correct gut intuition five or six times to turn the whole contest in your favor. When Berrettini appeared in press, he was equal parts disappointment and relief. “I think he missed three balls in the whole match. It didn’t give me that oxygen that sometimes you need,” he said. “But I think he surprised me, and I surprised myself also, how I was handling the level.” After a long time away from the sport’s elite, it must feel good to know you can still hang.

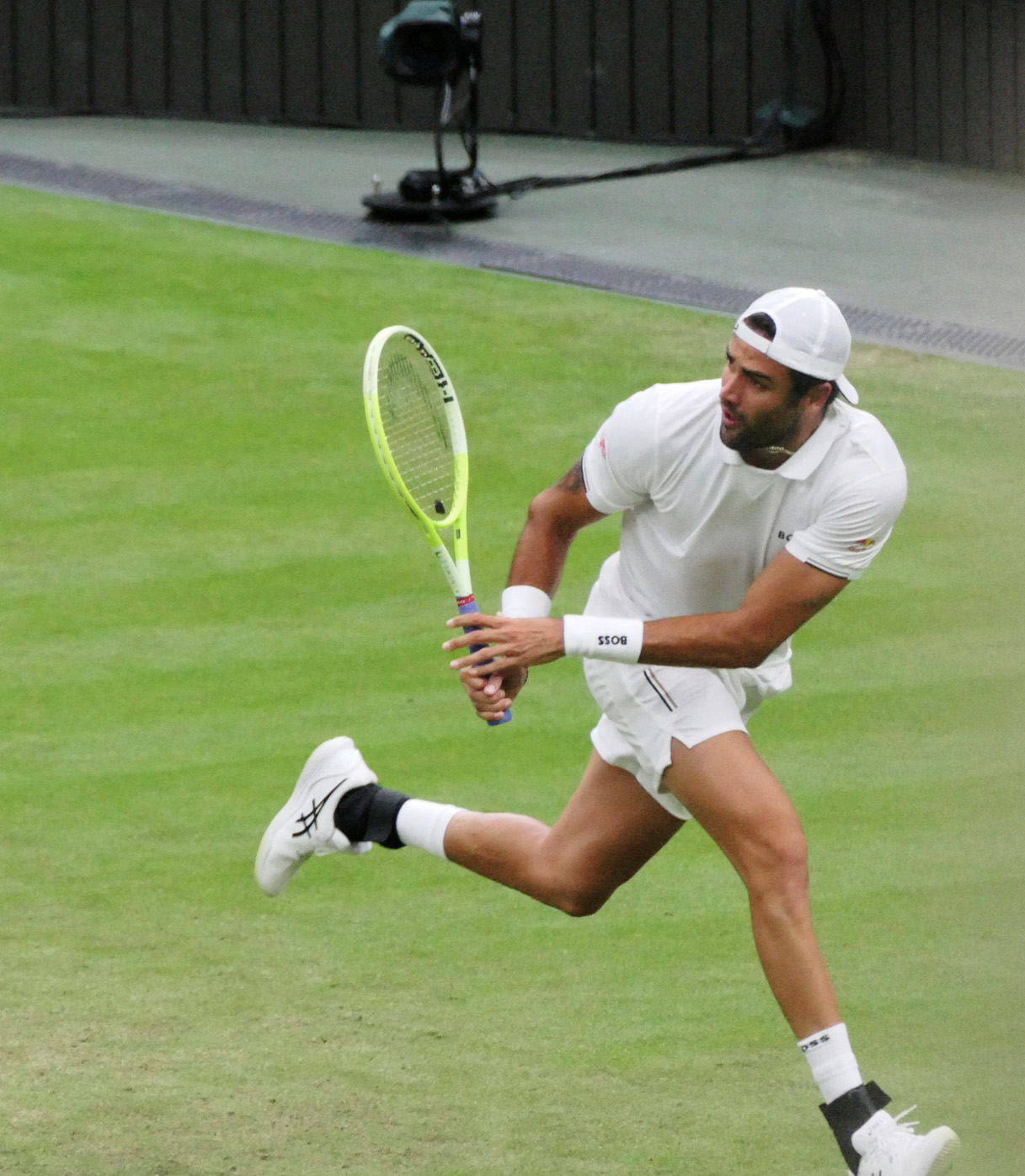

Berrettini battling. // Craig E. Shapiro

Berrettini battling. // Craig E. Shapiro